Zanan-e Emrouz (Today’s Women) Magazine has run an interview, conducted by Maryam Omrani, with Parviz Tanavoli, an internationally acclaimed sculptor, in its second issue out in July 2014. The interview looks into the development of Parviz Tanavoli’s artistic works with a focus on Saqqa Khaneh school of thought. It also focuses on his entry into jewelry and ornament production, analyzing the sociological aspects of the decorative objects. The following is an excerpt of the interview and its lead:

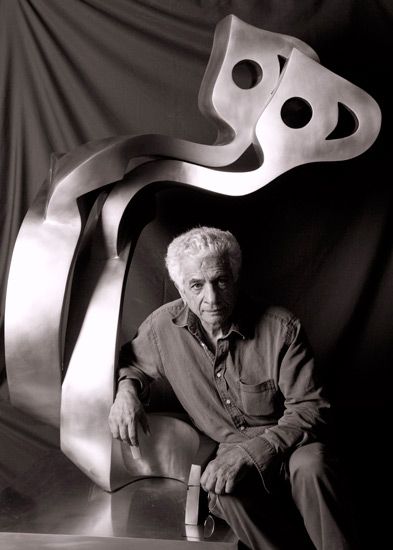

It is 6:00 p.m. June 5, 2014. I had an appointment with Parviz Tanavoli at his workshop located in his house in northern Tehran. I found a red-brick house with a yard awash with plants and sculptures which represent various periods of their creator’s artistic life. […]

It is stormy out there and the sculptures in the yard are covered with dust and dried leaves. A sculpture dubbed Heech (Nothing) which has sneaked its bust out of the cage in a southern corner of the garden leaning against the wall draws my attention more than other sculptures that sit far from the workshop. The master and I sit on dust-covered chairs in the workshop and continue our chat for hours thanks to his warm and good temper. […]

Tanavoli is part of Iran’s contemporary art history. He is a member of a generation of artists who tried – back in the 1960s and 1970s – to incorporate the qualities of modern art into Iranian art. Tanavoli is among the pioneers of the Saqqa Khaneh School, an artistic current he and his fellow artist masters of the time founded. They integrated the symbols of Iran’s traditional art and indigenous culture with global artistic standards of the time and created a new style; in other words, they tried their best to offer a modern definition of traditional and national aesthetics.

In addition to his main career as a sculptor, Tanavoli has always showed much interest in designing other items such as jewelry and decorative stuff. He has also brought together various collections of items from the country’s indigenous culture which merit attention from an anesthetic aspect. Drawing on the collections in question, he has put out some books, chief among them, the collections of Iran’s locks, surma holders, scales, scale weight stones, gravestones, charms and magic spells, etc.

The interview turned out to be more of a friendly chat than a specialized one-on-one meeting. It centered on feminine curiosities on the works Tanavoli has produced in the form of decorative items, among them the minimized sculptors used as pendants [hanging on bracelets]. Our chat also shifted to the history of non-traditional jewelries and decorative items and the way they were designed in Iran. He opened the conversation himself and here is what he said:

The other day when you talked to me about the link between decorative items and gender, I wondered why women like these ornaments but men don’t. Why is that women are interested in grooming themselves? Is it an internal need for them or they do so because men want them to? Anytime I thinking over this, I come to the conclusion that only men have run the affairs of societies over time and they have taken possession of everything in the world. Women too have been part of their possessions. One seems likely to decorate a thing the way they like when they have it in their possession. Perhaps, the balance would have been tipped and women would have decorated the men and bought them decorative materials if they had been in power, calling the shots and controlling the armies. Of course women’s desire to collect precious jewelry and decorative items could be somehow attributed to a lack of economic security on their part. A woman, with no business or job to earn her living, remained concerned about the uncertain future, especially if her husband had abandoned her.

In Iran’s public culture, or in the East by and large, there is a general tendency toward ornaments and embellishments. If you look at Iran’s traditional art, you would come across many tiny and dense designs which have been made merely for decorative purposes. Traditional jewelries, hand-woven materials and other practical items designed for daily use seem to have served such a purpose. Today, people’s taste has changed to some extent.

Yes, you’re right. It is so if we talk about jewelries independently. What has remained from different treasures such as those from ancient Greece, ancient Rome, ancient Iran, China and India does share common designing qualities. In eastern societies, decoration and makeup have mattered much and are still important. The reason behind this is perhaps the fact that women did not frequently go out so in order not to feel depressed they used to both wear decorative accessories and fill the house walls with different decorations and ornaments. They would hang carpets, tableau and calligraphy items on the wall. They would apply mirrors and mirror artworks inside the house. A careful look at their household items shows that the cooking pots, carpets and fabrics they used enjoyed an aesthetic style of production. It is true that men used to build these tools but it seems that they too wanted to see their wives amused, develop interest in their lives and the interior atmosphere of the house, and thus not miss the outdoors.

Now that you are talking about the aesthetic aspects the Iranians have employed in their items I remembered your collection of surma holders the photos of which have been released in a book together with their history. Are you saying that those surma holders were feminine devices?

No. They were not devices used only by women. The fact is that surma was not applied exclusively by women. Afghan and Baluch men still wear surma. In the past, surma was said to come with medicinal effects. According to an ancient Iranian text which has survived the passage of time, Cyrus the Great would instruct his soldiers to wear surma and blacken the areas around their eyes. The application of surma slightly differs from that of makeup. The people who lived in desert areas where the sunlight was direct and intense would put on surma to handle the light.

The ornaments remaining from the ancient times, for instance from the Achaemenid and Sassanid periods or later times, show that men too used ornaments for decoration. Is there any difference between these ornaments when it comes to designing patterns?

Men used decorative items as well, but I think the kind of ornaments they used was different. Men sought to highlight their masculinity and manly power through the jewelries they wore. They used to display their muscular upper arms by a metal ring [around them], or they would tie heavy metal rings around their wrists and necks. They would use much simpler decorative items. No precious stones can be spotted in their jewelries and ornaments. Generally speaking though, except for old stones such as emerald, ruby and the like, no other precious stone can be found in the ancient jewelries or those of the following periods. Stones and their use (in ornaments) are a new phenomenon. The application of stones such as diamond goes back to one hundred years ago. Decoration of engagement and marriage rings with gemstones like brilliant was first planned and introduced by British companies, and this suddenly sent the price of valueless gems like brilliant skyrocketing. But I think stones are soulless and lifeless and they are not very much different from glass, aesthetically speaking. Think about it. For example, imagine in China which is home to over one billion people, everyone decides to have brilliants in their marriage rings. This explains why this gem went global all of a sudden, something which saw these companies reap staggering profits. […]

Taking a look at the history of jewelries, we get to realize that it has been for long an issue for traditional artists or handicraft creators and that the jewelry making art has at times been regarded as an independent artistic field. Exactly when did people interested in visual arts as well as sculptors and painters start to design jewelries?

Well, some jewelries are attributed to certain artists of the Renaissance and post-Renaissance periods. Artists in general and painters in particular had and do have the talent to design jewelries but they had never been the producers of these items. Another guild would produce the jewelry, those who had mastery and had special tools at their disposal. In Iran too jewelry producing was a separate occupation. Traditional jewelry makers would design and produce their items all by themselves. At some point in time, jewelry designing became a mix of foreign jewelry and Iranian traditions. In the Qajar era, the import of French and Belgian jewelry was on the increase in Iran where [domestic] jewelry makers copied the imported items from time to time. At times the imitations were produced so delicately and skillfully that they looked even more beautiful and attractive than the real thing. And in another period industrial jewelries made their debut on the market.

As for my designs, I have no idea whether such a name is suitable or not. In our culture, “jewelry” is referred to a mixture of valuable gemstones and gold. These handmade items are too delicate and ornately rich to match my sculpture-like bronze and silver designs, unless we take into account their dimensions and functions in the form of rings, bracelets and necklaces. I have always showed strong interest in the sculptures which were made of stone, bronze and other materials in different areas in Iran in the first millennium BC, or the very tiny stone weights, horse gear or fittings or, let’s say, the designs which were not meant to be used as jewelry but their beauty was by no means less than jewels. I didn’t want to repeat or copy the ornate richness of traditional jewelry. Maybe I wanted to produce my works in a very tiny size ….

[…] Over the last 50 years we have seen practical designing by the world’s modern and post-modern artists who have created the items not related to their main profession such as sculpting and architecture. For instance, Zaha Hadid, who is known for her architectural works, does designing for decorative items and other tools such as house stuff, clothing items as well as shoes and footwear. What about Iran? How is it in Iran?

I dare to say that many people across the world who are active in visual arts are currently designing jewels as well. But I do not remember any in Iran. At first, it was only me who showed such an interest, I suppose. I started to make jewelry in the early 1960s. I don’t know of any other artists who have designed jewels on top of their main profession, for example sculpting. Back then I wanted to make the Heech sculpture in different sizes ranging from one spacious enough to accommodate one person to the size which could wrap around a wrist or a finger. Back then a woman who was a public office holder asked me to design jewelry for her. She wanted it because she had to take part in an official gathering in which ranking officials including ambassadors from foreign countries were also in attendance and she liked to have some unique jewelry on with Iranian designing, and not a Cartier design necklace or something with other European designs. The same lady gave some semi-precious gemstones to me. I did some designing and it marked the beginning of my job. I did some of those designing patterns for my wife and some other people. One of them is the very “Heech” ring which was widely welcomed. […]

Do the materials you use for making jewelry differ from those used for producing sculptures? Do you make use of more expensive metals such as gold and silver as well?

I do use bronze instead of gold. I seek to get my message across by using such primary materials. I want to say what matters is the work of the artist and not the materials he or she uses. […]

Do you know anything about your customers? Do you have a special audience in mind when you work on your designs? I mean a special social group.

No. I don’t think about any special group of people while working, but instead I think about making my items in a way which everybody can easily use, for example different sizes of rings and necklaces and this does not cover a special group of people in society. I don’t have any information on the exact number of those who buy my works, but they are usually top earners or high-income groups in society. Compared with sculptures, the price of decorative items is much lower. The upside of the jewelries is that they look as if they are friends with people. They are close to us since they are on our fingers. They go from place to place with the person who carries them. They even go on trips with their owners. On the other hand, you need a vast space to hold a sculpture, whether it is placed in the garden, inside the house or in any other place. It cannot accompany you wherever you go and you cannot take it on a trip with yourself.

Now that you talked about the friendship between an individual and his or her jewelries and their attachment to human body, it crossed my mind to ask you how the jewelries affect the personal identity and help distinguish between its owner and the others. For example, a woman who wears an expensive piece of jewelry tries, in one way or the other, to show she is different from other people, or the person who has put on the Heech ring regards herself or himself somewhat distinct from other people from a cultural point of view. Both share one thing: they like to be different.

It has been the case in all societies and throughout all historical periods. Suppose, for example, the jewelry an artist like (Alexander) Calder designs is used by some. They must be distinct. Also bear in mind that their price is likely to have risen multifold since their production date. I don’t think a change of taste in using jewelries could be indicative of the change of time and a change in the spirit of those who wear them. With the modern jewelry and decorative items being received warmly, one can come to the conclusion that the mood of the Iranian women has changed from traditional conservatism to adventurism and to acceptance of the challenges of the modern world. Moreover, women display much interest in producing jewelry and decorative items. Girls and women account for 70 percent of my students in Mah Mehr Institute. The figure does not apply to jewelry courses alone. It covers other courses as well.

When did your classes resume in Iran and when did you include jewelry designing in the courses you teach?

Well, for years before the Islamic revolution I had taught in university but after my return to Iran I held a first round of classes in Mah Mehr Institute back in June 2006. If my memory serves me well, about two years later courses on modern jewelry designing were introduced. I’d like to say some words about my students, although they may not find their way to the magazine. Perhaps the magazine decides one day to publish reports on every single of them. Around 100 modern jewelry makers have been trained in my classes. They have been very much successful recently, both in holding exhibitions and in selling their works. Recently, fifteen students of mine held an exhibition in Mashhad which, to my disbelief, was widely welcomed. Incredibly these modern jewelries are widely received by people; most of them were sold out on the opening night. The same group has held exhibitions in Tehran, Kuwait and Paris. I was with them for some of those shows. I’m very happy that a modern jewelry nucleus has been born in Iran and now it is in its teens. These students have gone much beyond where we do stand now and I’m certain that their mother lode of knowledge would grow by the day. […]

Let’s come back to the question of women. Given the public culture and traditions, many Iranian artists, you included, produced some works back in the 1960s and the 1970s that are known as the Saqqa Khaneh School. Is there any trace of femininity in the works you produced back then?

You know, men are the theme of my works and I have usually placed women next to men. My sculptures mostly have a very masculine identity; in other words, a man who always has a desire for women. My works, namely Farhad Koohkan and Poet, show that these men had a desire for women. The men in my works never do without women; they have been always in love with women. Perhaps women have been given no figurative personification or representation in my works, but their traces are seen everywhere (he laughs). I don’t know what you would have done if men weren’t around, but I wouldn’t like to live if women were not in the world.