Reflecting the campaign for forgiveness, a 27th issue of Ayeh magazine ran an article on “Qisas and Pardon” which includes a few interviews. The first interview was with Ali Jamshidi, a former Criminal Court judge. The dialogue centered on ways of securing consent from the victim’s family and on efforts to talk them out of seeking Qisas. The second interview was with Nima Nakisa, a former goalkeeper of the national football team and a social activist. In the space of three months, his efforts to seek pardon from victims’ families for those convicted of murder have seen 27 death-row inmates walk away from the gallows. The third and last interview was with another Hujjat al-Islam Qazanfari, a former Criminal Court judge, now a member of parliament’s Judicial Committee. The following is an excerpt of the article:

Civil activists join forces with courts to seek pardon from victims’ families for those convicted of murder, hoping to hand them a second chance to live.

Over the last few months, Islamic compassion has given life back to a number of death-row inmates across the country. If attempts to win pardon for Balal, a convicted killer in Mazandaran – a province in northern Iran – had not received the media coverage it did, there would have been no manifestation of Islamic compassion in the provinces. However, what happened indicated that forgiveness is an option. It all started when the host of a popular TV sports show called on the family of a young man who was killed in a street fight by Balal to pardon him and waive their right to Qisas [an-eye-for-an-eye Islamic retribution law]. Those appeals persisted until the execution day. Balal stood on a chair on the gallows with the noose around his neck. When the mother of the victim walked to him, everyone thought she was about to pull the chair from under his feet, but much to everyone’s surprise, she slapped him in the face, took the noose off from his neck and forgave him. Her motherly forgiveness was followed by a wave of unexpected pardons. In short, Balal’s pardon was the beginning of serial forgiveness across the country.

Qisas is the religious and legal right of a person who has lost his/her beloved one, and no one can or should deny the bereaved such a right. However, religious experts say, “Qisas is not a hard-and-fast rule which leaves the family of the murder victim with only one option. In fact, they have three choices: they can ask for Qisas, opt for blood money, or forgo both and pardon the murderer. Still, Qisas is a social right that cannot be denied.”

Time and again, I have heard that the pleasure associated with forgiveness can never be found in payback. Qisas is not exclusive to Islam. In fact, it did exist in non-divine schools preceding other religions, but Islam turned it into law for Muslims.

It’s true that Qisas is a right, still God speaks nicely about how sweet forgiveness is. “Time and again, We have heard that the pleasure associated with forgiveness can never be found in payback. Qisas is not exclusive to Islam. In fact, it did exist in non-divine schools preceding other religions, but Islam turned it into law for Muslims,” said Hujjat al-Islam Mohammad Mortazavi. Verse 178 of Koran’s Al-Baqarah Surah reads: “You who believe, the law of retribution is prescribed for you in cases of murder, but if the heirs of the killed person forgive the killer, then they should demand blood money within reason, and the killer must pay with handsome gratitude; this is mercy from your Creator and nurturer; so after this, whoever transgresses the limits, he shall have a painful torment.” The void emanating from the loss of a loved one in the hearts of bereaved mothers, fathers and children can never be filled. It will be nagging for the mother of Abdullah, as well as for the mothers of two other murder victims, one in Takestan – a city in Qazvin province – and the other in East Azerbaijan province. Yet, as experts say, it would be much better to opt for the sweetness of forgiveness rather than the bitterness of revenge.

That set the stage for a first “National Celebration of Forgiveness” event in June 2014. The gathering was intended to praise the efforts of those who were actively involved in seeking pardon for young people who were convicted of murder. In attendance were Hujjat al-Islam Sayyed Hassan Khomeini, a host of state officials, artists, sportsmen, social activists, and a number of judges who had introduced innovative ways to secure pardon for young people.

Hassan Khomeini led off his speech with a poetic line by Hamid Mosadegh. The line cursed “anyone who is opposed to us becoming one.”[The grandson of the founder of the Islamic Republic] said, “If we want forgiveness to become common practice, we should promote the culture of forgiveness, and the journey down that path starts from ourselves. Those in authority should do the same thing and try to forgive those whom they might hold grudges against.

“Those who pardon have a right as far as the murderer is concerned. By waiving this right, they give the death-row prisoners a second chance at life. In addition, they have a right as far as society and every single of us who lives in it are concerned. Through forgiveness, they show us that the community should be purged of spite. One who forgives does not just pardon the killer, he also gives us dignity,” he added.

Pointing out the impact of such gatherings in promoting forgiveness in society, he said, “One of the results of meetings as such is that a seed is planted with the hope of growing. A seed planted in soil first sprouts, then turns into a sapling which later grows into a productive tree that contributes to the future of society.A spite-free community lives with no issues. Every journey to progress starts with baby steps. We should start being good on the inside. When we expect the victim’s family to waive their right to Qisas, are we ready ourselves to let go of our small demands? For example, when it comes to driving or, more generally, inourinteractions with family and relatives, to what extent do we exercise patience? Kindness should be injected to society somehow.”

Ali Jamshidi, a former Criminal Court judge

What is the difference between Qisas and the death penalty?

Qisas is the punishment for murder, more specifically for killing a Muslim. In other words, if a non-Muslim kills another non-Muslim, he won’t be sentenced to Qisas. However, if either a Muslim or a non-Muslim murders a Muslim, he will face Qisas. The charges a person who has killed a Muslim faces cover both the private and public aspects of the crime s/he has committed. The punishment meted out for the private aspect of a crime is Qisas, while the public retribution is three to 10 years in prison. However, if a defendant is charged with crimes which endanger public security such as rape, waging war against God, or drug trafficking, based on the type of crime and its severity the court hands down the death penalty. […]

Judges of criminal courts and prison officials try until the very end to secure pardon. Of course, such efforts are made for cases involving Qisas.

How far do judges and prison officials go to seek pardon for a death-row inmate?

When a case is sent to the courthouse to have the verdict enforced, a few sessions are held and the victim’s family is advised to practice what is recommended by Islam and pardon the murderer. These sessions carry on even after the verdict is upheld and the victim’s family comes to the prison to witness the execution. Judges of criminal courts and prison officials try until the very end to secure pardon. Of course, such efforts are made for cases involving Qisas. […]

Do those efforts continue even as the inmate is already on the gallows?

Seeking pardon does not know any bounds as far as time and place are concerned. We intend to save a person from death, that’s why until the very last moment even when the noose is put around the neck of the convict, we try to talk the victim’s family out of Qisas. Mind you, we do our best not to leave it to the last moment. To that end, we organize some sessions to secure clemency for a remorseful convict. Even when the convict is on the gallows and there is a sense that the victim’s family is slightly willing to forgive him, we try to prolong the process with the hope of having the convict pardoned. […]

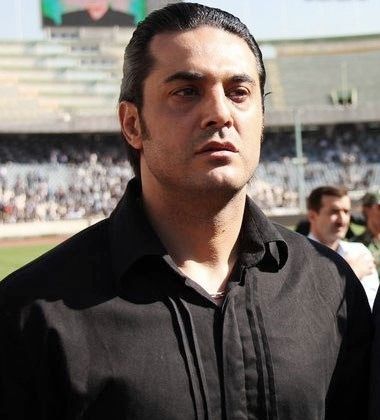

Nima Nakisa, whose efforts have saved the lives of 27 people sentenced to Qisas

It was in February 2014 when Nima Nakisa, the former goalkeeper of the national football team and Tehran’s Persepolis club, made the acquaintance of Judge Amirabadi, the head of Tehran Criminal Court. Later that acquaintance saved 27 convicted murderers from the gallows. Judge Amirabadi, who was then the acting head of Tehran Criminal Court, asked Nakisa, the vice-president of the Dispute Settlement Council, to start seeking pardons from victims’ families. He was never given a letter of appointment, but before long he established a record for himself in terms of winning pardons from victims’ families and saving convicted murderers from the gallows. In just three months, he managed to save 27 people from death. Now, Nima Nakisa is sitting down with us for an interview on murder, murderer and Qisas.

No one has the right to question Qisas. It is a religious and legal right of the victims’ families. That right is explicitly underscored in verse 45 of Maidah Surah in the Koran which cites the fact that God has put life in Qisas for people. At the same time, it’s said that if anyone remits the retaliation by way of charity, it will be for him an expiation of his sins.

Mr. Nakisa, have you spent all your days in Tehran courts over the past 3 months?

Yes, about four or five hours a day.

You mean you went to the courthouse every day to be introduced to a victim’s family to secure their pardon?

No, I usually read the cases myself and picked one to pursue.

Did you give priority to cases which deeply moved you?

Not really, I only got myself involved in certain cases. I keep away from the cases involving premeditated murder or rape. My efforts are aimed at saving those convicted murderers who have killed without malice aforethought.

So you have your boundaries as far as seeking pardon from the victims’ families is concerned.

I don’t wish to judge people, but I am not interested in cases involving abduction, premeditated murders, rape or horrific killings. Yet, I believe some killers lose their control in a fit of temper, and should be given a second chance to live. […]

Unfortunately, some who wish to encourage people to pardon, question their fundamental right to Qisas, either intentionally or unintentionally. What are your thoughts on it?

No one has the right to question Qisas. It is a religious and legal right of the victims’ families. That right is explicitly underscored in verse 45 of Maidah Surah in theKoran which cites the fact that God has put life in Qisas for people. At the same time, it’s said that if anyone remits the retaliation by way of charity, it will be for him an expiation of his sins. […]

Have you ever thought about social implications of such pardons? How does a murderer behave when s/he returns to society?

One does undergo change when a death verdict is issued in their case. If pardoned, they could be the source of good. Once I came across a murderer who memorized the Koran in prison and turned into a totally different person, but he was sent to the gallows. Had he been pardoned and returned to society, many could have learned from him and moved in the right direction. Let me stress the point that as a matter of fact, in this day and age, lots of values have lost their luster. We have a rich and effective religion and culture. However, in the face of the cultural onslaught, lots of our values have been pushed to the sidelines. I believe we should revive our humanity, our principles and our culture. We have great role models like [war] martyrs who came from all walks of life and became national heroes as a result of their actions.

In conclusion, I want to briefly address the families who ask for Qisas. I want to tell them that Qisas is the right which is given to them by God, and nobody can doubt it. But nonetheless, I do want them to put the execution on hold, consult with experts, and avoid making a decision they will regret for the rest of their lives.

Some people abroad are critical of the lawful, legitimate and Islamic right to Qisas, whereas those who are unmindful of the emphasis Islam places on forgiveness argue that such pardons have harmful effects which can later pose a threat to society. Such opposite views made us conduct an interview with Hujjat al-Islam Musa Qazanfari about the position of Qisas in Islamic retribution laws and also about efforts to consolidate the recent campaign for forgiveness. The MP representing Kerman province in the Islamic Consultative Assembly described the present Qisas law as “complete”, and said that pardoning a convicted murderer plays a major role in easing violence and stigmatizing criminal activity, even though there are some who believe otherwise.

Hujjat al-Islam Qazanfari, a member of parliament’s Judicial Committee

Since the start of a forgiveness campaign which got underway when Balal, a killer from Mazandaran province, was given clemency, different people have taken different positions and some foreign media have criticized the concept of Qisas. First, tell us briefly about the position of Qisas in the Islamic retribution law.

Under Islam, Qisas is a legitimate verdict and a legal right for the victim’s family. As a matter of fact, it’s an obvious and explicit law which cannot be questioned or doubted. It’s explicitly stated in the Islamic retribution law that Qisas is the right of the victim’s family, not that of the government. Yet, the law also grants the family the option to waive their right to Qisas and instead reach a compromise with the murderer to either pardon him in return for blood money or an amount bigger than the official figure, or simply forgive him in exchange for nothing. All that should be decided by the victim’s family. As for the public aspect of the crime, the government can only subject the pardoned murderer to punitive measures and Ta’zir [punishment administered at the discretion of the judge] which can range from a few months to a year or even more in prison based on the decision of the judge. However, the judge cannot and will not have the authority to overturn the verdict of Qisas and grant the convict clemency. […]

Under Islam, Qisas is a legitimate verdict and a legal right for the victim’s family. As a matter of fact, it’s an obvious and explicit law which cannot be questioned or doubted. It’s explicitly stated in the Islamic retribution law that Qisas is the right of the victim’s family, not that of the government.

From your perspective, how permanent the ongoing campaign for forgiveness will be?

When I was a judge hearing homicide cases, I would always build on the Koran and Hadith [the record of the sayings of Prophet Muhammad] to urge the victims’ families to forgive. Islam lays great emphasis on forgiveness. The recently-launched campaign to seek clemency is truly praiseworthy, whether the media contributed to it or other factors were at play. Anyway, I do hope it will persist. I am not sure media publicity can have a long-lasting and sustainable effect on the campaign. Its impact will be short-lived, because the loss of a child for the parents is so tremendous that the media could not keep playing an effective role in seeking pardon in the long run. However, if we intend to have those sentenced to Qisas pardoned, we should draw the attention of victims’ families to Hadith, Islamic compassion and the beauty of forgiveness. On the execution day and even prior to that, prison officials, the elderly, and in cases similar to that of Balal even artists should take action. […]

There are some who argue that if every murderer is pardoned, then the crime will lose its stigma. Do you agree with such an argument?

I strongly disagree with such contention. In fact, I have a compelling reason for my opposition. I was a judge. I have often seen the conditions of those sentenced to Qisas in prison and in courts. Thugs who draw machetes and kill are usually transformed after a verdict of Qisas is handed down and they are sent to prison. They are usually in a state of extreme ignominy and misery. […]

On the eve of execution, the prisoner on death row is isolated from his fellow inmates and is told to ask God for forgiveness, and make a will. He spends a night or two in solitary confinement, waiting for death. It is impossible not to undergo change. In some cases, because of those changes in the behavior of convicts and their humiliation and remorse, the victim’s family eventually voices consent to spare them. So I believe that forgiveness will never destigmatize crime.

To what extent do you think such pardons can reduce the number of murders in society?

Forgiveness will have its own impact on society. We witnessed such an effect after Balal – who killed Abdullah Hosseinzadeh in a street fight – was pardoned and saved from the gallows. On the execution day, after he was pardoned in Noor – a city in northern Iran – in a symbolic act lots of young people who had knives on their person took them out of their pockets and threw them to the ground. That is nothing but the positive role of forgiveness in cutting the murder rate.