A 17th issue of Andisheh Pouya (Dynamic Thought) magazine, which came out in July 2014, featured an interview with Roshan Vaziri, the translator of The Heavenly Lady, a collection of short stories by Polish writers. The monthly magazine seized the opportunity to bring up the subject of the culture and lifestyle of the Poles and their long-rooted ties with Iranians in a chat with the translator and her husband of Polish origin. The lead to the interview and excerpt of it come below:

Roshan Vaziri studied medicine in the University of Warsaw many years ago. She married a Polish man there and then returned to Iran with her husband, Leshek Wozniak. More than five decades into his stay in Iran, Mr. Leshek views himself as an Iranian. Roshan Vaziri too has developed a liking for Poland and its people.

A one-month trip to Poland is a fixture in their annual timetable, the souvenirs of which are books written by Polish authors that Roshan Vaziri renders into Persian. The Heavenly Lady is the latest of these books, a collection of six short stories by five Polish writers, selected and translated by Roshan Vaziri.

The release of the translated version of the book was one good reason for a friendly chat with the translator. Since the interview was to touch on issues beyond the book and talk about the culture and life of the Poles, her husband of Polish origin was also on hand for the friendly heart-to-heart. […]

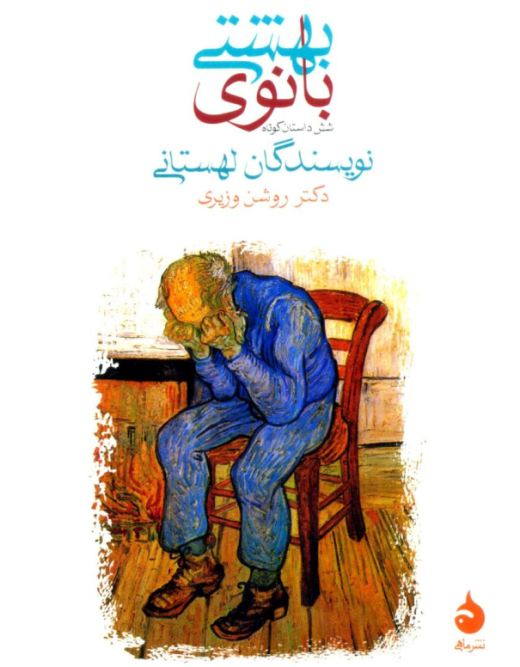

The final story in the book focuses on the final days of Vincent van Gogh. As a matter of fact it is not a story; it is a literary piece on the renowned Dutch painter. What motivated you to pick this piece and place it along the other five stories?

Roshan: Yes, you’re right. It is not a fiction; it is just a feature on van Gogh. I loved this piece. I do like van Gogh. I picked this item and put it beside the other five because my life centers on love. The piece in question properly features the dying moments of van Gogh and his tragic life, not to mention the fact that it is a brilliant literary work.

In a foreword to The Heavenly Lady, you have cited efforts to familiarize the Iranian readers with the Polish literature and its great literary figures as a criterion for selecting the stories of this book. The question is why you have collected only six short stories for the book, whereas the fictions are appealing enough to make the book still thicker. I think it would have been better if you had translated a few more stories for the book.

Roshan: The main reason why I found only six stories sufficient for the book is my own state of health. My eye problem didn’t let me skim through Polish stories and come up with more fictions for rendering. That I have chosen a small number of stories for the book has another reason as well. We shouldn’t forget the fact that text screening remains in place here, so one always needs to bear in mind that not all books can get a permit to go to press. […]

Four out of six stories in the book depict the sufferings and hardships a Pole goes through outside of his homeland. We can say they narrate the agony of a displaced person or an emigrant who is far from his birthplace. Why is the pain associated with emigration highlighted in Polish literature?

Roshan: Yes you got it right. Emigration plays a key role in the characterization of people in these stories. The point is that emigration has the most influence on the culture and life of the Poles. A sense of being a Pole and homesickness stays strong with Polish emigrants. For instance, about 13 million Poles and those of Polish descent live in the United States.

Leshek: Many people in Poland emigrated to other countries in the late 19th century and early 20th century due mainly to poverty and financial straits. That’s why emigration, homesickness and nostalgia have become an inseparable part of the Polish culture. Emigrants [or the Polish diaspora] who left the country prior to and after the 1980 Solidarity Movement in Poland have recently started to go back home, especially after the country’s economy began to grow.

Mr. Leshek! Are you a Polish emigrant too?

Leshek: I wasn’t, or let’s say I emigrated for the sake of love. On the other hand, I chose not to live in a Communist-ruled country. The elder members of my family had been anti-Communist from the start. It was back in the Second World War when my grandma insistently refused to use the term “the Polish government”. Instead she would say that it was the government of Russians.

One of the issues the stories as such impart to the readers is that religion has had deep roots in the culture and public beliefs of Poland. Is the role religion is said to play in Poland the direct result of the anti-faith measures taken during the Communist rule? Or has it been there untouched all through the Polish history?

Leshek: Church has always played a powerful role in Poland. The part it played during the Solidarity Movement was of great consequence. People used to go to church to display their protest at the Communist regime, even those who lacked any religious beliefs would join the churchgoers [to take part in the protest]. The church put up stiff resistance when Communists were in power. Many priests were imprisoned, but rarely did they work with the Communist government which was in office.

Roshan: In fact, the church served as the bastion of protest back then.

Did the marriage between the revolutionaries and the church continue well after the (downfall of the) Communist regime and the rise to power of the new government?

Roshan: The situation is now different from what it was in the past and the church is no longer a key cultural player in people’s lives. New issues have surfaced in people’s social life, which have pitted individuals against the church. The church still matters in regulating social ties and the personal lives of people, though. […]

In The Trumpeter of Samarkand the audience reads a narrative on the presence of Poles in Gulags [the Soviet forced labor camps] and their release which sees them head southward and into Iran. It’s a story a narrator in Tehran tells his friend about a public belief in Samarkand. Has any story been written on the time those Poles spent in Iran?

Leshek: In Iran several books have been written and compiled on these emigrants. The Poles did stay in Iran for two years. Back then, professor [Saeed] Nafisi was the first person who studied the culture of these people. The Poles who came to Iran from the Gulag Camps hailed from affluent and intellectual families that had been sent to Siberia by the Russians. They published two newspapers when they were in Iran. The Poles do love Iran very much. Thanks to the hospitality of the Iranians, the Polish refugees feel indebted to their hosts.

Roshan: Iran, Isfahan in particular, turned out to be like Heaven on Earth for the Poles, especially in the wake of the gruesome experience they had in the Gulag Camps. The Trumpeter of Samarkand makes mention of the Iranians’ hospitality and their warm welcoming of the Poles. It may be interesting for you to know that I had been learning the Polish language for two months with a Polish woman who had married an Iranian army officer and it was well before I left for Poland to pursue my studies.

The majority of the Poles stayed in Iran, got married and led a normal life here. They have now passed away. A large number of Polish men left for the battlefields right after their release from the Gulag Camps. Some Polish women and children left Iran after World War II. The memory of Isfahan, its pleasant sunshine and tasty dishes were matchless for those refugees who had come from the Gulags. The Poles did love Iran very much and for them the memories of the Iranian city have stayed.

Are you suggesting that Iran was in fact like a hotel for the Poles?

Roshan: Exactly! A number of Polish women tied the knot with Iranian men and therefore their children are of Iranian origin. When the Solidarity Movement was on the rise in Poland, some of these young people went there. It is surprising to know that Poland had traditional ties with Iran for about 54 years and the history of their mutual ties goes back to Safavid King Shah Abbas I.

Leshek: Yes! A Polish businessman has built the Armenian Church in New Julfa neighborhood in Isfahan.

Has any book written by Iranian authors been translated or published in Poland?

Roshan: Yes! Actually the number of such books has recently increased. Another interesting point is that a large number of Polish students do learn the Farsi language. Many students are learning the Persian language in Krakow and Warsaw universities. I think the moving spirit behind this is their strong interest in ancient Persian literature. When I was a medical student there, I taught Persian in the University of Warsaw for one year.

At that time the number of students who liked to learn Farsi was not high. It is also interesting that I had trying times in Poland at a young age, but the memory of that country has lived on in my mind thanks to its kind people. So that’s why my love for Poland is more than that of Leshek’s. I’ve found it necessary for myself to visit Poland once a year. I am crazy about Poland, because I have spent my young days, although it was tough, in that country. […]

From among the six short stories, which one do you like most?

Roshan: Latarnik (The Lighthouse Keeper) [by Genrik Senkevich]. It is an extraordinary, romantic story. Narrating the life of an old lighthouse keeper, the writer reveals the in-depth impact poetry leaves on the culture and viewpoints of the Poles. It may sound hard to believe, but pieces of poetry are published in all magazines and publications in Poland. Poetry is still of great significance to the Poles and substantially affects their lives.

Leshek: I do like The Lighthouse Keeper more than other stories in the book. It does not give an account of the life and fate of a Pole alone; it also explains the fate of an entire generation of the Poles.

If so, the Poles must be very romantic?

Roshan: Yes, very much so. I translated this story because I think Iranians would like it due to the fact that poetry counts much in their lives too.

Leshek: The Poles are widely said to be good poets, the ones who do know music well and outdo others in ballet, but they don’t know much about economy.

Roshan: But in practice, it has proved otherwise. Poland rose above the economic crisis of 2008. It is the only country in Europe which has posted economic growth in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. It managed to escape the fate that befell Spain, Portugal and Greece. Poland is a successful model of liberal democracy. Close on the heels of the Solidarity Movement, Communist and Socialist economies were replaced by an open market economy. To tell the truth, the rulers sent shockwaves through society and the big shock saw many people sustain huge losses.