When one becomes a parent – even a middle class, white parent with all the privileges denied the majority of those whose tragedies litter our news feed – we see our sons and daughters in the gray corpses of Palestinian children, in the broken bodies of drone victims, in the slaughtered Yazidis, in the black, unarmed child hit six times by cops whose ostensible duty is to protect and serve, in the angry kid who charges up to a cop and says, ‘Kill me now. Shoot me now” just moments before nine shots ring unhesitatingly through his brain, his lungs and his other vital organs, rendering him a bleeding, empty, dead corpse on the sidewalk (one whose corpse, nonetheless, must be cuffed for good measure). Every day is an overwhelming exercise in restraining my horror, empathy and moral outrage into 800 words or less, with fewer cuss words and tears than the first draft. But then there are the exceptions. The times when something happens in the news that is so horrific, so vile, and so unpleasant, that I fail to feel anything at all.

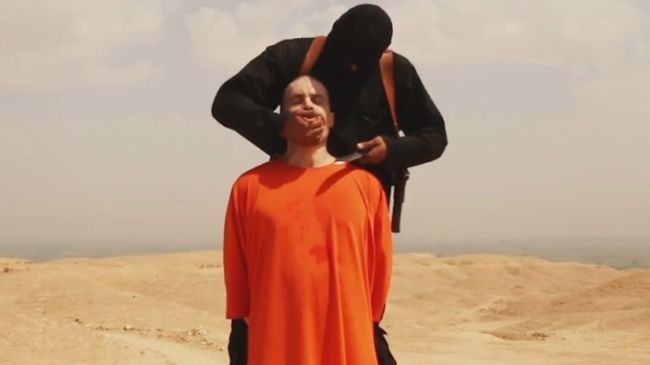

I was editing an article at my desk last night, my teething eight-month old baby playing happily with wooden blocks on the floor at my feet. My husband entered the room and casually asked: “What are you working on?” I looked up from a window I’d just opened: a sun-bleached landscape, shaven headed white man, orange jumpsuit, a black-clad terrorist standing next to him holding a knife. I smiled at my husband, distracted, as the video streamed and the man in orange awkwardly read from an auto-cue off camera. “I’m just watching that journalist gets beheaded. Can you take the baby outside?”

We could make this an article about how I – a young, white mother in Venice Beach – have become inured and desensitized to violence through my exposure to the internet, but to be perfectly honest, I don’t think my massively inappropriate reaction to James Foley’s brutal and horrific death is about the internet, films, movies, video games or the proliferation of violent images I’m saturated with, day after day. I think my inappropriate reaction to the murder of James Foley is a consequence of my daily, unwilling participation in the unrelenting violence of the United States of America, a country which – with every black life stolen, with every drone strike sanctioned, with every body held without trial, with every black life ruined in the prison industrial complex – proves itself the most violent perpetrator of all.

We are ordered to believe, time and again as Americans, that the violence sanctioned by our government is justified. That it is for our greater good. Collateral damage, we are told, is an essential part of our national and personal security. Yet the fall-out – particularly when it concerns white Americans – is barbarous and inhumane. In this enduring mythology of good vs. evil which our government streams relentlessly to the public, the cop holding a gun and shooting Kajieme Powell is behaving in an exemplary way, while the man holding a knife and slicing open James Foley’s threat is, in contrast, a barbarian, a beast, less than human.

When is violence “good”? When is violence “justified”? When is violence less horrifying, less sick, less disgusting, less inhumane, than other violence? When it is inflicted with one’s hands, or indirectly via a sensor operator, a grounded pilot in the baked Nevada desert, a man who gets up at the end of his shift, steps into the bright sunshine and drives his station wagon home past a sign which says “Drive Carefully: this is the most dangerous part of your day”? Is violence better when it’s performed in the dark against a large number of indiscriminate targets – human beings, we should say – the videos held in secret, only spilling into the light of day when a whistle blower steps forward or a FOIA reveals the truth? Is violence worse when it is against one individual: performed for the camera, taped, elaborate, ritualistic and dramatic? Is violence better when it is casual and habitual, inadvertently immortalized for the world to see? When the weapon is a knife or a gun? When it is done in defense or offense? State sanctioned or revolutionary? When it is retribution or vindication? When it is done in the name of one’s nation, or one’s religion?

I am reminded of that oft-quoted Martin Luther King speech, cited so often in the wake of the riots in Ferguson, most amusingly (and incorrectly) by Fox News who seemed to suggest MLK would have a moral and ethical issue with the protestors in Ferguson:

“It is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society. These conditions are the things that cause individuals to feel that they have no other alternative than to engage in violent rebellions to get attention. And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard.”

A riot is also the language of the oppressor turned back whence it came. Pacifism and nonviolent resistance are the only morally defensible positions for victims to be in, not that this assures their protection.

I did not have a problem watching the video of James Foley’s murder. I did not avert my eyes. I did not find myself – as I had before, with Palestinian children or Michael Brown – mentally pasting my son’s eyes into those of the victims. Rather, I saw Foley as myself.

“Jim Foley’s life stands in stark contrast to his killers,” Obama said on Wednesday. “Let’s be clear about ISIS. They have rampaged across cities and villages killing unarmed citizens in cowardly acts of violence. … No faith teaches people to massacre innocents. No just God would stand for what they did yesterday and what they do every single day.” He goes on: “Their ideology is bankrupt. People like this ultimately fail. They fail because the future is won by those who build and not destroy.”

Obama describes the ideology of ISIS as “Bankrupt” as “slavery to the empty vision”, seeming to imply that the US, in contrast, offers – what? Great moral credit? Oppressors to a full reality? Following on from nearly two weeks of uprisings in Ferguson, the irony is not lost on many of us, particularly black Americans still struggling against the systemic racism that White America continually fails to acknowledge. In this narrative of Empire, James Foley is held up as a hero, applauded for his “bravery”. As someone who has been told, multiple times, that I was “brave” to go to Afghanistan, I can assure you it is certainly not heroism or bravery which drives people like James Foley and myself to these far flung corners of the world, to places where the empire goes to die and we might too, surrounded by languages we cannot speak and cultures we know about only through google, to report about conflicts and other horrors in a way pre-determined by the nature of whatever publication or organization will pay for our words. Call it nihilism or optimism, thrill seeking, war tourism, adrenalin addiction, or call it, simply, a commitment to ‘the truth’, it does not cancel out James Foley’s humanity, his life, his legacy, nor the unbelievable dignity and grace of his last moments on earth, captured for all the world to see. It does not justify extremists or find excuses for their actions. But it does, heartbreakingly, remind me once again that white lives like mine belong to a firm narrative of conviction, an infallible belief in our own moral and ethical superiority, while black and brown folks are merely the pawns in a game of empire, driven ever more incessantly towards an ineluctable conclusion. That conclusion could be a rebellion – but is more likely to be “a riot”. That conclusion could be the radicalization of large numbers of people – but will probably be “the creation of terrorists”. That conclusion could be an act of warning, a signal to those in the West to cease with their Imperialist meddling – but will more than likely be “an unforeseen terrorist attack” just like 9/11.

The sad truth is that the future does not belong to people like James Foley, whose lives are spent – like mine – chasing the next great tragedy, disaster, death and outrage to write about. The future does not belong to our children, depicted in grainy images on Facebook walls with holes in their blood-bleached, dust stained corpses. The future does not belong to the new, and yet overwhelmingly familiar horrors being churned up by yet another chapter in US Imperialism. Future implies we have somewhere to go: some momentum that propels us to a new destination, a new day, something different. Yet the future belongs only to this same interminable hamster wheel of cyclical violence, where the US, the emperor of the world systematically destroys black and brown people at home and abroad, and justifies it in terms of “defense”, ratcheting it up whenever that defense provokes any reaction which is not nonviolent.

Ruth Fowler is a journalist and screenwriter living in Los Angeles.