The burial traditions in historical periods are known through archaeological evidence and sacred texts like the Zoroastrians’ Avesta as well as Pahlavi texts.

With the recognition of the Zoroastrian religion in Iran, body burial was strictly prohibited and the only way to eliminate the corpses was to place the deceased in rows so their bodies would be feasted upon by birds of prey.

In a Zoroastrian religious text, which is a collection of religious rules and instructions, there are references to the ways to treat with the bodies of the dead. According to these texts, the dead should be put in structures known as dakhma to be feasted upon by birds of prey, because the burial or burning of the corpses would cause the sacred elements of water, soil, and fire to become dirty and it is forbidden to do so.

However, according to the researchers, even in Zoroastrian texts, there are indications that a significant number of people opposed the change in funeral practices, which resulted in penalties. Given that the time passed between the burial and the exhumation, only physical punishments were imposed on the perpetrators, which were practically subject to fines.

According to the findings, for a long time, it was generally thought that burial was more based on putting the corpse outdoor. But extensive scientific studies revealed that the Sassanids, in addition to the tradition of placing the body in the open air, used other burial practices. This can be interpreted in relation to religious communities within the Sassanid Empire and perhaps related to the class division of society in this era.

According to Samer Nazari, a graduate of archaeology at the Isfahan University of Art and his colleague, “the coexistence of religious communities including Christians, Jews, Manicheans, Buddhists and other religious sects in the Sassanid community is one of the main reasons for the diversity of burial practices in this era. At the end of the Shapur I era, the Zoroastrianism was the official religion of the country, but Manichean religion, along with other emerging sects should not be ignored. This comes as Buddhism was also spreading in the East, and Christianity and Judaism were expanding in the western regions.”

Based on the available information, it is not possible to attribute the burial practices specifically to a particular group, but according to the teachings of the Zoroastrian School, we are aware of the prohibition of burying bodies for the purpose of keeping water and soil clean. Thus, the most dominant burial method during the Sassanid era was to put the deceased body in a dakhma, or towers of silence.

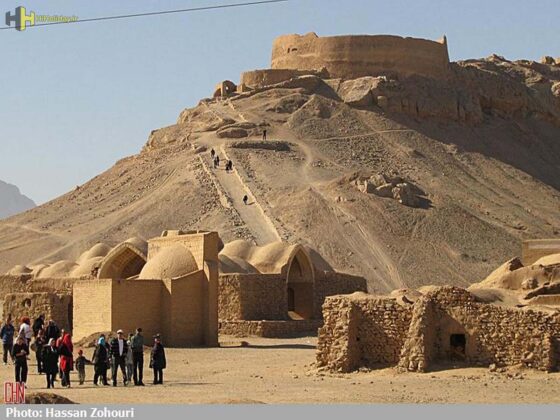

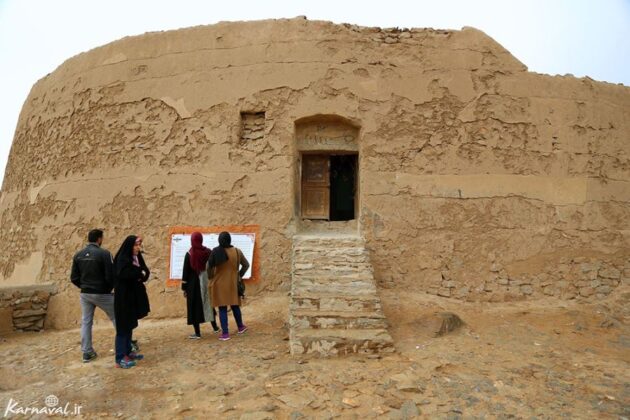

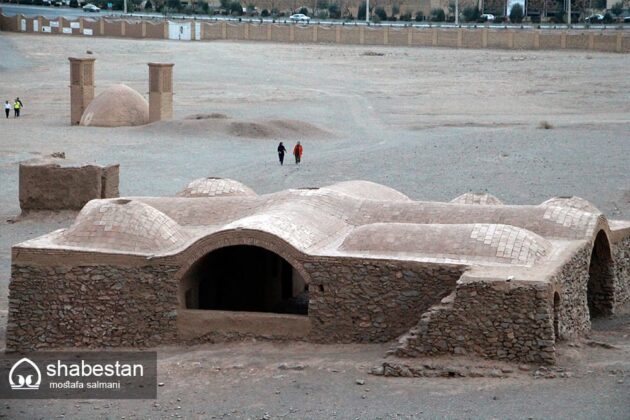

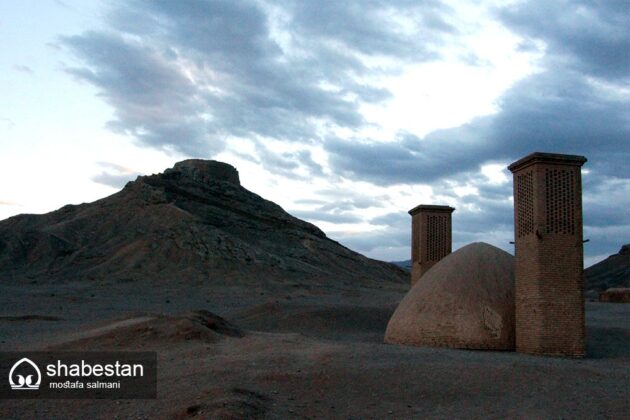

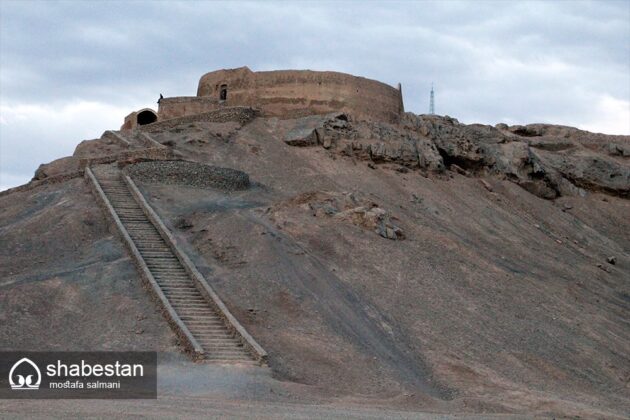

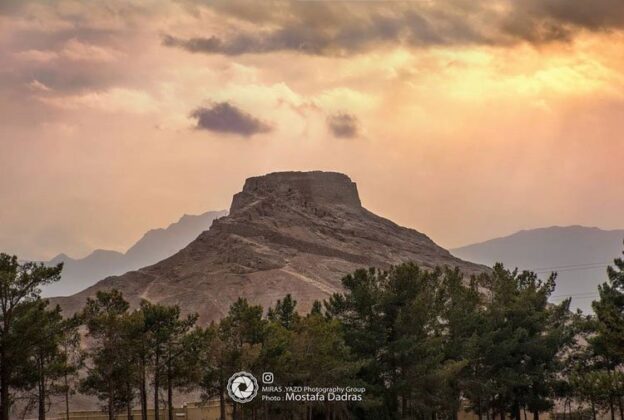

The dakhmas or towers of silence were common until Pahlavi era (20th century). At the time of Pahlavi, the dakhmas were shut down and turned into a burial chamber. But some of the dakhmas are registered as national heritage with domestic and foreign tourists visiting them. The most famous Zoroastrian dakhma is in Yazd province.

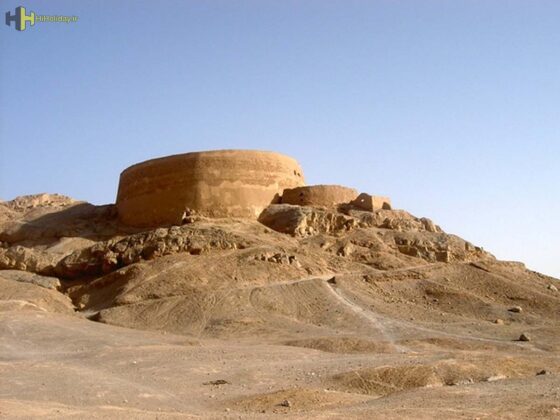

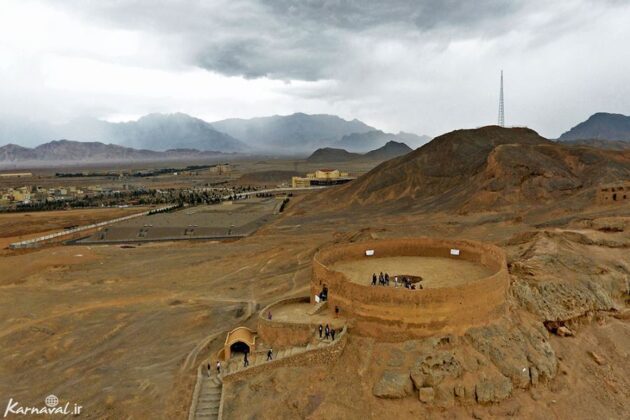

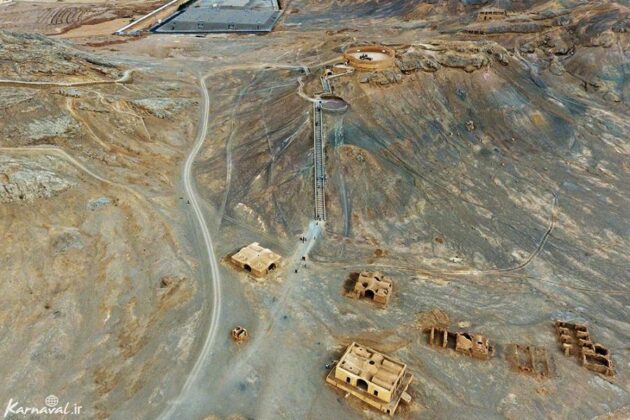

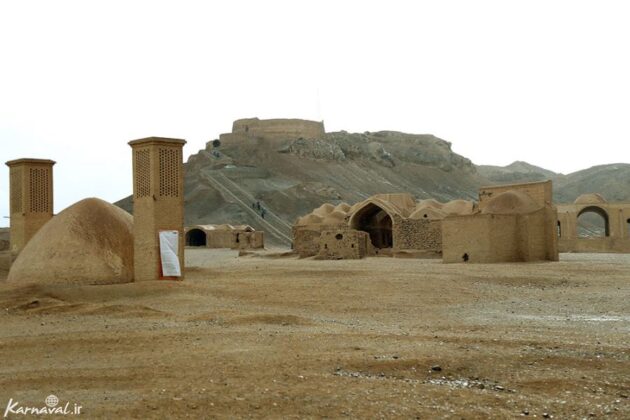

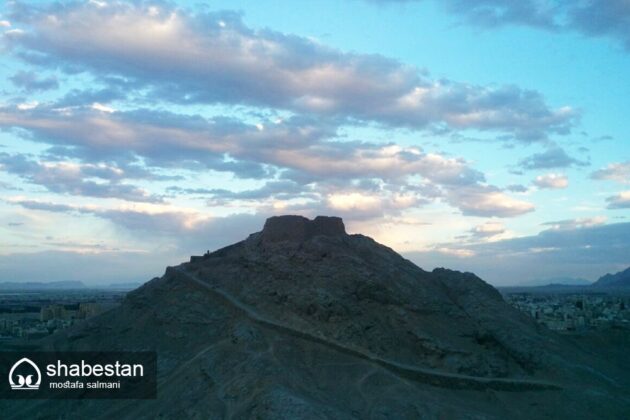

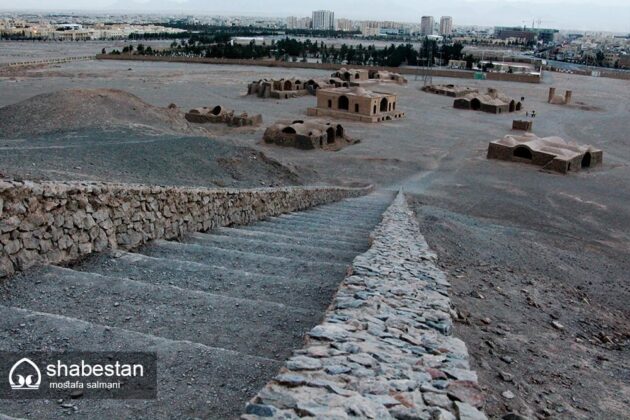

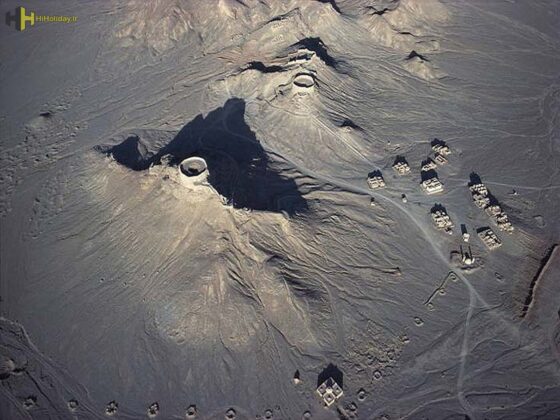

Zoroastrian dakhma is known as tower of silence. This dakhma is located 15 km south-east of Yazd near the Safaeiyeh area and on a low-altitude mountain called the mountain of the dakhma.

Although there are Zoroastrian dakhmas in Tehran, Kerman, Sirjan, Isfahan, Taft, Ashkezar, Ardakan, Fars province, etc., the dakhmas of Yazd have more visitors as they are located in the religious capital of Zoroastrianism close to the city and other monuments.

Zoroastrian Dakhma or Tower of Silence

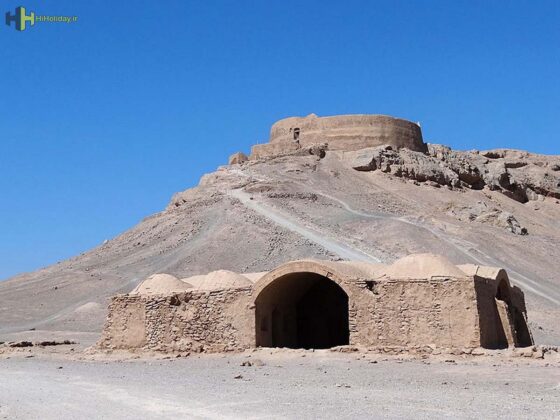

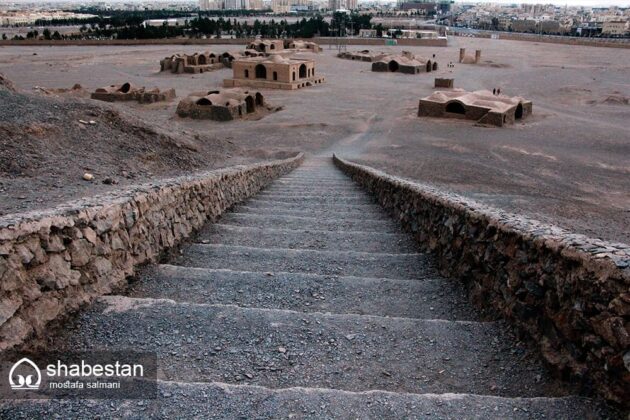

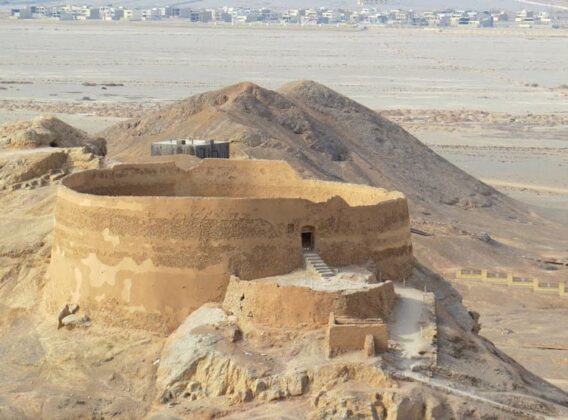

In the past, the site had two dakhmas, which, according to historical documents and Zoroastrian words, both were used for a period of six months. One of these structures is the Maneckji Limji Hataria dakhma, or the Great Maneckji, which is located on the left.

Maneckji, known as Maneckji Sahib, travelled to Iran during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, as the representative of “the Association for the Improvement of the Zoroastrian Conditions in Iran,” in order to reduce the pressure on Zoroastrians. Zoroastrians still owe their existence to his efforts.

The second building is Golestan dakhma. During the Qajar period, the difficulty of passing through the mountainous road of the Maneckji caused problems for the burial of the corpses. That is why the Golestan dakhma was built in smaller dimensions. This dakhma could be seen 150 metres west of the Maneckji. The diameter of this dakhma is 25 metres and the height of the wall is 6 metres from the surface of the hill.

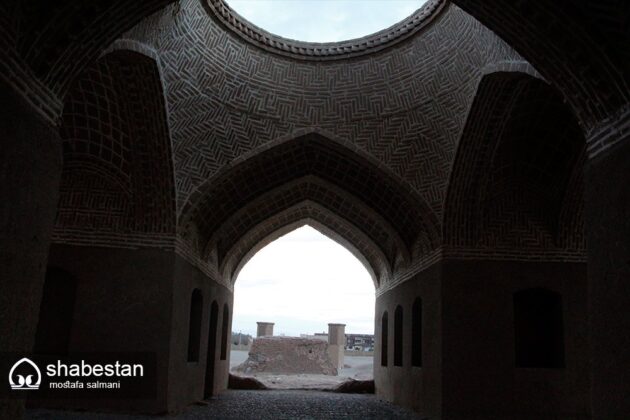

The inner surface of the Zoroastrian dakhmas is flat and rounded, all covered with large boulders and consists of three parts: feminine, masculine and childish. Perhaps it’s not bad to know that the end of the circle space, which is attached to the wall around the dakhma, is for the corpses of men, the middle part is for women and the inner circle is for children.

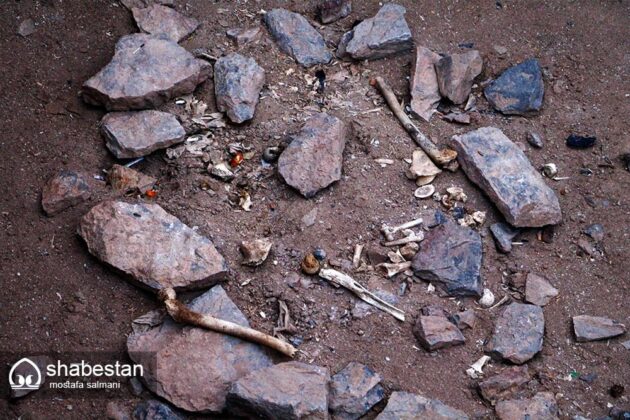

The bodies were placed on these slates according to their gender, and the birds of prey, especially vultures started to eat their flesh. After eating the flesh and becoming completely dry under the sun, the bones were poured into a well in the centre of the circle, called the bone well, to turn into dirt.

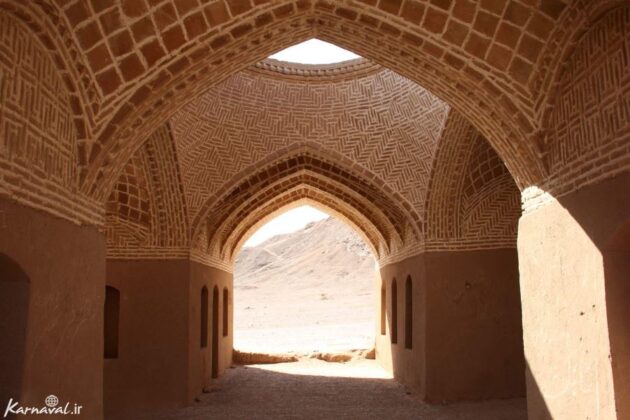

All burial practices from leaving the body inside the dakhma until its disappearance lasted about six months to one year. When the dead were placed inside the dakhma, it was customary to mourn, wearing white clothes for three days in ruined buildings next to the dakhmas known as “Khileh”.

Interestingly, in a documentary entitled “The Lovers Wind” made by the famous French director Albert Lamorisse in 1970, part of it was dedicated to the Zoroastrian dakhmas of Yazd. At that time, the dakhma was still open.

Below are photos of this Zoroastrian dakhma retrieved from retrieved from various source: