He lost one of his eyes to World War II. For years, he was a shopkeeper. At the age of 70, he had an accident and slipped into a coma. When he came to, he changed course and like a young man took up painting. Over time, he turned into a sculptor. He would make sculptures on the sidewalk and put them up for sale right there.

It looked as if his eye, blinded during the war, found a way to the world of peace and could now delve deeply into life through the prism of art. How this 90-year-old man defined life and human beings was the subject of a report posted on honaronline.ir on January 4. The following is a partial translation of the item:

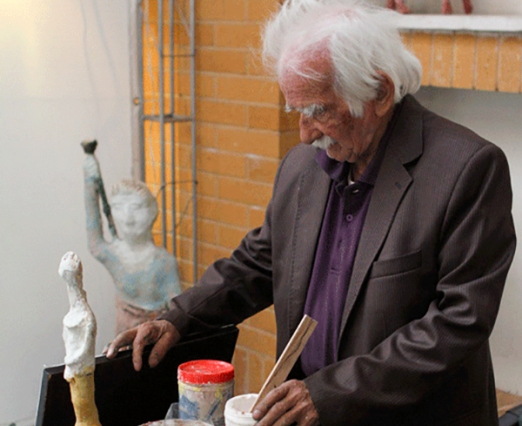

A few months ago, when he held an exhibition of his sculptures in a Tehran gallery, I went there for a visit. There he told me that the passion for life was not limited to a specific age and that he hadn’t been and wouldn’t be scared of death ever. In his 90s, he did everything on his own. I saw him on his feet for hours to create sculptures. Unfortunately, I have just heard that the artist has passed away.

A few months ago, when he held an exhibition of his sculptures in a Tehran gallery, I went there for a visit. There he told me that the passion for life was not limited to a specific age and that he hadn’t been and wouldn’t be scared of death ever. In his 90s, he did everything on his own. I saw him on his feet for hours to create sculptures. Unfortunately, I have just heard that the artist has passed away.

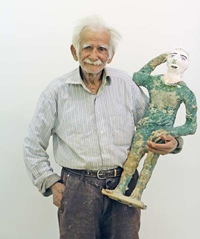

If one day I were asked about the most astonishing characters I have ever come across in my life, undoubtedly, Hassan Hazer Moshar would be among the first who come to mind. The two sculptures I bought at his last exhibition keep reminding me of him, a character whose lifestyle and uniqueness cannot be summed up in a few sentences.

However, for a start, suffice it to say that he took up self-taught art at the age of 70 which by itself is an interesting story. In his early 90s he would stand on his feet for 13 hours to paint, make sculptures or deal with a group of university students. I am sure it will strike you as interesting to hear that after living in the capital city for five decades, he still maintained his Gilaki accent which was reminiscent of friendliness in human nature.

“My feet won’t feel exhaustion as long as my mind is not consumed with fatigue. What matters is that the brain should not be overwhelmed with weariness,” he would say.

“I began to take art seriously after I had an accident in the vicinity of my carpentry workshop near Azadi Square in Tehran where I hit my head on a stone and fell into a coma. When I came around, I could no longer work, so my daughter rented out the shop to my apprentices and did not let me work.

“However, I could not stand doing nothing. I somewhat knew how to paint and gradually learned more from my daughter who is a painter. Since then I have spent almost every waking moment on this art. At first when I started making sculptures, I did not have a workshop so I worked on the sidewalk and then sold my works there, too.

“One day I was sitting under an overpass in Tehran making a fairly big sculpture when a man came to me and asked if I had created it by myself. When I told him that I was the sculptor, he bought it from me and placed an order for more sculptures. Afterward, he put them on display in an exhibition in Tehran. The man was Kambiz Derambakhsh [a cartoonist and graphic designer]. He still has my sculptures and won’t sell them. When it comes to creating artworks, I have always felt free and comfortable. If an artwork did not turn out the way I liked, I threw it away,” said Hassan Hazer Moshar.

“I don’t approve of old men sitting idly by on park benches all the time. Even if you have nothing to do, doing something seemingly pointless is much better than sitting idle. It’s never late to start doing what you want. Even at the age of 90, life can be seen as a package full of dreams. When unwrapped and used up, one should be able to introduce himself as a [good] human.

“People should not be driven by greed and worldly affairs. If they are consumed by such things, they will be lost. If people think long and hard, they will notice that everything will end up in death. Therefore, they will understand that they should leave behind something by which to be remembered. To me, art is a vehicle for immortality. Nonetheless, art can help keep alive well-known figures like Saadi and Hafez – two famous Persian poets – or a person of humble background like me,” he added.

The disabled veteran who had lost one of his eyes in World War II said, “Beauty is only skin-deep. I never thought of myself as someone who doesn’t have an eye. I even married after I lost sight in one eye.

“Now that I am alone, I do my daily routines all by myself. I get up early in the morning, go for a walk, prepare a light meal, and then start working. My house has two rooms. I use one of them as workshop and the other as living room. Time passes, life goes on and one should apply logic. One day you weep and the other you smile. That’s the secret to life. That’s why it is not worth feeling concerned.”

That day he talked about several other things. Now that he is gone, I feel devastated by his loss. I am sorrowful not for him because I knew he was not afraid of death, I am sorry because in his absence, there is something missing in life. In fact, life has lost him.