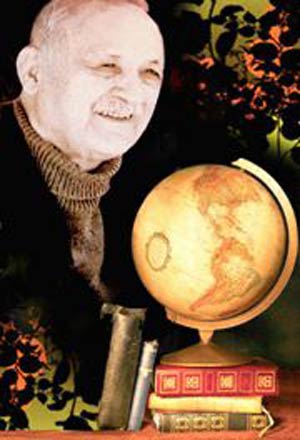

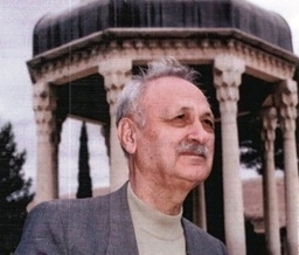

Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob, a prominent Iranian historian and author was born on March 19, 1923 in Borujerd, western Iran. Before being admitted to Tehran University in 1945 to study Persian Literature, he taught at schools of his hometown. Ten years after admission into the capital’s flagship university, he received a Ph.D. under the supervision of Badiozzaman Forouzanfar. In 1956, he began to teach Islamic History, History of Religion, and History of Sufism courses at Tehran University.

He also taught arts courses in Tehran before moving abroad where he held faculty positions, among other places, at prestigious universities such as Oxford, Sorbonne, Princeton, and University of California. He penned several books on literature as well as on Persian and Islamic history and translated several others. Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob passed away on September 15, 1999 in Tehran at the age of 78. To mark the anniversary of his demise, Etella’at newspaper published an article this unforgettable literary figure had penned. The following is the translation of the article in its entirety:

Almost 200 years ago during the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, prominent French author and philosopher Montesquieu used an extremely sarcastic language, which was a fixture of his Persian Letters, to prompt Parisians, astonished by the strange stories involving Rica and Usbek, to curiously ask each other “How can one be an Iranian?”

When the nonchalant Parisians put down the book, their curiosity which was likely to have been a product of their imagination, slipped away too. The thousand-plus unanswered questions Montesquieu had in mind about the chaotic times he lived in seemed to push that question into the sideline. I came across the same question during a French literature course in school; I have since thought about an answer again and again.

How can one be an Iranian? No doubt, ethnicity and race are not the determining factor in being an Iranian. Since the reign of Achaemenians, many different ethnic groups including Persians, Scythians, Turanians, Greeks, Arabs and Tartars have mixed in this land and the idea of having a pure Iranian race now sounds childish. Still the generations that have emerged as a result of their intermixing have all lived in Iran and for Iran. And even if they had pure blood circulating in their bodies, they could not have been any more Iranian.

Although language plays an undeniable role in the evolution of Iranian character, assumptions that residents of this land are Iranian simply because of a language which is free of borrowed words would be nothing but a dream. The fact that some Iranians frown on the use of foreign words may stem from their patriotic zeal, but their insistence [on declaring Farsi off-limits to foreign words] is bound to limit our linguistic maneuverability and deprive our culture of what it has achieved over the centuries.

The fact of the matter is that the pinnacle of our Islamic culture which came before the Mongol invasions and conquests was mostly Iranian. One cannot simply build on the fact that a language has been influenced by a foreign language to suggest that itis far from being a source of pride.

Throughout this period, Iranian culture has been a jewel in the crown of Islamic culture. And the presence of some Koranic words in Farsi is proof that Iranian culture has had spiritual influence in the world of Islam. It could have been impossible for Iranian culture to sweep the entire world of Islam from the Ottoman Empire all the way to the Indian Subcontinent and not borrow a number of Arabic words that have been used in the holy Koran.

Can you think of one language which has been as exposed as Persian to foreign words and has maintained its purity? In everything which is described as Iranian heritage and Iranian culture, there are traces of other ethnicities, but this has not compromised the integrity of the Iranian heritage.

Iran’s role in the world civilization

The world civilization owes Iran a debt of gratitude big enough to immunize it against any doubt about the integrity of Iranian culture, both before and after Islam. Humanity is indebted to Iranian culture when it comes to literature, arts, morality and religion.

In literature it is not just fable that owes Iran a debt of gratitude. Goethe, André Gide and almost all prominent writers of other genres such as Romanticism and Parnassism have learned a thing or two from Iranian poetry, drama, and storytelling.

As far as music is concerned, Iran left an indirect impact on European music through Arabic music. In architecture, the Iranian role in bringing together the dreams of the east and west was conspicuous even before the emergence of Islam. Researchers believe that in the absence of Iranian architecture, the Byzantine architecture would not have made so much progress. (1) During the Islamic period, Taj Mahal, this marble mausoleum, which symbolizes the peak of artistic talent, was partly built by architects who had received training in Iran.

The religion and ethical standards Iran has introduced to the world are of great importance too. In a world where ethical ideals of Assur and Babylon had promoted savagery, the constant struggle between good and evil in which human tendency toward the former would be viewed as contribution to building a virtuous world amounted to an ethical revolution for the entire humanity.

Centuries before the emergence of Christianity, Mithraism turned fraternity among humans into the cornerstone of the bond among its followers. The idea of integrating major faiths, which seemed elusive even as recently as during the monarchy of Nader Shah and Akbar Shah, was very close to materialization under [Prophet] Mani.

In promoting Islam, Iranians strove as much as other Muslims did. Nowhere did Islamic mysticism manifest itself more concretely than in the works of Attar, Mowlana and Hafiz. The investment Iranians made in the global culture market was big enough to create unprecedented credit for Iran in spiritual transactions on the international stage. It is true that Iran owes the world a lot for helping it build a magnificent heritage; what Iran has offered the world in return is so significant that its absence will definitely interfere with the way the world handles things.

From dream to reality

No doubt, just like a civil society, no member of the international community can play in the real world the role of an imaginary castaway like Robinson Crusoe and serve as a jack of all trades and view itself as totally independent of others. In a world where all nations are linked through a visible or invisible chain, Iranians cannot limit themselves to their past and keep dreaming of reviving the Achaemenian and Sassanid dynasties.

In the past, Iranian culture has borrowed positive elements from other cultures and has in return lent them valuable things. This tradeoff which manifests Iranian flexibility and zeal has lent its culture an air of integration, linking it with eastern and western cultures.

But Iranian culture has a noble human element that symbolizes its spirit. It is thanks to this human element that Iranian culture finds its way into other cultures, and even soothes the aggressor and helps blend it in itself. This human element has been so delicately built into each and every Iranian custom that identifying and separating it is now difficult.

Iranians are Iranian without having to be a supermarket of jealously and deception like Usbek in Montesquieu’s Persian Letters; without being as abased and foxy as James Morier’s Hajji Baba and without being infatuated with the West in every aspect of life like the protagonist of Jafar Khan has returned from Abroad. In the absence of literature, natural delicacy, flexibility and intellectual tolerance and without their historic quest for justice, Iranians won’t be Iranian.

It is true that the level of Iranian politeness and delicacy might at times verge on flattery which is typical of slaves. But morphologically speaking, the shamelessness and promiscuity that have come to our land along with infatuation with the West can be a legacy of the snatch-and-run attitude of the cavemen. Tolerance might be at odds with the totalitarianism which is in practice in many modern societies. In the past the same practice helped create a vast empire for Cyrus and failure to uphold the same principle played a role in the defeat the empire suffered at the hands of Alexander.

Justice and tolerance

In Iranian mythology, Zahhak and Afrasiab, who symbolized injustice and deviation from the path of Ahura Mazda, are said to be Aneran – which means non-Iranian. Because of the injustice they did to fellow humans, they are not viewed as Iranians by those who have created those myths. Justice and tolerance which Zahhak and Afrasiab have disregarded are the principal components of Iranian culture.

The first Iranian empire which was founded by Cyrus had a constitution which enshrined tolerance and respect for the viewpoints of others. I have described it again and again as Cyrus-style tolerance. Thanks to the same tolerance, the Greeks were given a chance to make their presence felt in the Achaemenian land. As a famous Greek Philosophy historian (2) says what had been banned by Athenian narrow-mindedness came into existence in Ionia, part of Achaemenian territory where the earliest Greek philosophy books were written. One should credit the proverbial Iranian tolerance and respect for the viewpoints of others for that.

Thanks to inevitable incidents, this spirit of justice and tolerance did not materialize, but it remained a pillar of Iranian culture in the post-Islamic era. That Shiites supported the administration of justice as a pillar of faith caused a rift between them and Sunnis. Besides, books on literature, morality and politics praised justice as the loftiest of causes.

As for tolerance, the impact was so huge that mystic figures described the differences among religions as a war of words and Hafiz said the war involving 72 nations was only an excuse. The conflict erupted because they failed to identify the true path and thus opted for myth. Centuries before Sartre and Russell, our mystic figures objected to war. In a world where Christians formed an alliance with Mongols to kill Muslims, Sa’di said, “All humans are members of one frame.”

If Iranians have had an opportunity to offer something to the rest of the world, it has come at a time when justice and tolerance have prevailed in their society. For instance, at a time when Medieval Tartar justice was in place and these two elements were absent from Iranian society, colorful flatteries which were designed to deceive the fool came in the form of qasidas by Farrokhi, Anvari and Zahir. Mystic concepts which fill Iranian poetry with lofty humanitarian concepts came from scientific forums and Khanqahs [places for spiritual retreat and character reformation of Sufis] which provided shelter to justice and tolerance when they were in trouble.

It is true that at some stages in history like during the reign of Anushirawan, supporters of Mazdak, [who was a Zoroastrian prophet] were mistreated. Those things happened when justice and tolerance were somewhat forgotten. But radical approaches were not in line with the spirit of Iranians, and scholars of the past never willingly approved of such stupid measures and injustice. These rash measures pale in comparison with the relatively sustainable moderation of Iranians.

Those who are familiar with different aspects of human nature in dramatic situations definitely know that the most moderate of individuals go through critical moments too. Sudden excitements of a moderate soul do not take away his/her justness, similarly fleeting episodes of immoderation in the long history of an ethnic group are no proof that it does not believe in the principles of justice and tolerance.

Iranian culture has a language whose integration of a number of non-Persian words with Dari lends it dynamism and makes it unforgettable. It is true that this language is not pure. Does the fact that individuals such as Abu Moslem, Shah Abbas and Nader Shah were partly Arab and Tartar make us doubt their being Iranian identity?

The language Hafiz, Sa’di, Khayyam and Mowlana employed was the true language of Iranian culture. Inclusion of a number of non-Iranian words in this language will do nothing to diminish our interest in it. It is said that when British Orientalist Edward Browne came across a scientist who could speak Farsi, he’d set aside any other language. “We need to speak in Farsi, because when you speak that language you feel your language is more humanistic in nature.” Don’t the Iranians who speak in foreign languages with their children or those who write in English in workshops and hospitals feel ashamed when they hear this quote from Edward Browne?

A closer look at Iran’s past

When I think about Iran’s past, I take pride in the fact that the Iranians have not killed fellow humans or destroyed the world in the name of religion or freedom; in the fact that they have not massacred the residents of territories they have captured; in the fact that they have not enslaved their enemies; in the fact that they have offered shelter to the Greeks and have accommodated Armenians; and in the fact that they have freed Jews and their prophets from captivity in Babylon.

I also take pride in the fact that they have not launched Crusades and have not held Inquisition hearings; in the fact that they have had nothing similar to Saint-Barthélemy and have not used guillotine to behead their opponents; in the fact that they do not view gladiator fights or bloody games involving angry bulls as entertainment; in the fact that they have not uprooted native Americans and have not pushed Boers to the edge of extermination; in the fact that they have not developed torture machines to frighten their opponents; and in the fact that if there were some horrible punishments in practice during the reign of certain Sassanid kings, they have always looked at them as evil phenomena. The fact that unlike other old nations Iranians have not exhibited moral defects gives me a sense of calm and pride.

How can one not be Iranian?

If the question of Montesquieu and curious Parisians is once again posed to me – How can one be an Iranian? – I have a clear-cut answer; one which comes in the form of a question itself: How can one not be an Iranian? I believe the new generation and the ones that follow to see the continuity of Iranian culture and history can proudly produce the same answer. To do that they need to hold on to this moral and human element that already exists in Iranian culture. Besides, at a time when lofty human goals are tumbling, we need to make as much effort as possible to keep hopes alive that Iranians in the future will remain as impeccable as those who have lived in the past.

However, if the day comes when the intervention of modern-day figures limits the dynamism of our language and deals it a blow, when our delicate literature gives way to violence and compassion-free, shameless behavior, when our quest for justice is replaced with revengeful savagery, when Cyrus-style tolerance is replaced with censorship of ideas, when our love of good is supplanted with selfishness, when the curiosity of Parisians is coupled with discontent and indignation and the same question – Iranian? How can one be an Iranian? – is bitterly asked, I hope that the tone of those who ask this question is full of praise for those who love Iran.

(1). Talbot Rice, “Persia and Byzantium” in “Legacy of Persia” 85.

(2). Zeller, “Outlines of the History of Greek Philosophy” 1955/23.