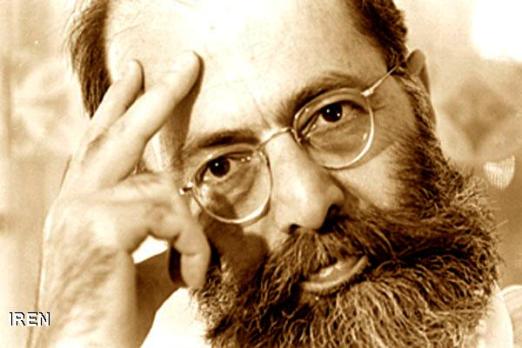

Translating the comments of a veteran translator and journalist is certainly a gamble for Iran Front Page, particularly at a time when we have just hit the road. But we at IFP are more than willing to take the risk of inviting his assessment. The following is an excerpt of an interview Mohammad Ghaed has given to Iran newspaper’s Sayer Mohammadi. The interview, along with its lead, appeared in the August 24th issue of the daily, which is run by the Islamic Republic News Agency:

A Farsi translation by Mohammad Ghaed of The Guns of August, an account of World War I by American historian and author Barbara W. Tuchman, was published by Mahi Publishing House earlier in 2014. It is to be reprinted shortly. Ghaed is very good at writing articles. Apparently his journalistic background gives him an edge over fellow translators.

The appearance of his name on the cover of any book is enough to set the seal on its success. His translation of Powers of the Press: The World’s Great Newspapers by Martin Walker was reprinted several times by Markaz Publishing Co. and is now a sought-after book on the market. So are the books he has penned himself including The Diary and Oblivion, along with Injustice, Ignorance and Those in Limbo on Earth and Suffering and Healing, which have been reprinted a few times each.

[…] What is it that modern man and history-lovers can take away from books?

As Benedetto Croce has put it “All history is contemporary history.” When we contemplate the past and review what has already happened, we are actually thinking about the present. When in our thoughts we go back in time to the Qajar era, to the 19th century Tehran or to the early 20th century when the First World War was still raging, we wonder what we would have done or felt if we’d lived in those circumstances.

In the absence of contemporary history, many past things would lose their importance, either partially or totally. We lose our interest in old things because they are in the past. That we spend money on antiques is because they take us back to an atmosphere that combines the past and the present.

I believe what is important about this book, or about World War I in general, is that it amounts to a rejection of subjectivism and voluntarism that suggest humans developed thoughts which in turn gave shape to history and changed the world.

In this book the world has undergone change, but humans hold on to views which are similar to those of their ancestors. By that, I mean, similar to the thoughts of kings, rulers, prominent politicians, generals and war commanders, not ordinary people.

With the outbreak of World War I, technology took a great leap forward. Internal combustion engines, Zeppelins, machine guns and long-range guns became available on the market. The theories of the 18th century turned into industrial products, and industrialists were mass-producing them.

For instance, the inventions of Thomas Edison dating back almost 200 years were mass-produced. Things were progressing exponentially. Progress on one front translated into more rapid headway on others.

But the prevailing attitude in societies and among rulers dated back to centuries earlier. They were of the conviction that modern cannons and machine guns would do the same things elephants and muzzleloaders did in the past, so they embarked on conquests that were once unimaginable to Napoleon and Frederick the Great. Imagining the practical results of fast-paced developments and understanding their aftermath were almost impossible for individuals or even for an entire generation. They needed experience that seemed unfathomable even when it actually happened.

You sound like a person who views the Great War as an end to an era. Do you think the outbreak of the war was inevitable?

Moral inevitability is not the same as natural inevitability. When a cluster of cells grows, it may become too big for the container in which it is located. The cellular growth which is exponential is designed to help the cells survive. […] Ironically it is both simple and complicated at the same time.

That happened in the First World War and in the run-up to the downfall of the Shah [Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]. The system the [Iranian] monarch established grew bigger and bigger. In parallel, the population grew, the number of universities increased, people got more educated and urbanization took off. As a result, the political shell which was unable to accommodate all that imploded.

By the early 20th century, European societies had grown bigger and more complicated. Quality had followed in the footsteps of quantity toward change. Universities, which were a German invention, had found their way across the Atlantic to the US.

Modern-day universities can be described as a joint invention of the Germans and Americans. Bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. degrees as well as dissertations were non-existent. For centuries, universities from Agora in Greece to Sorbonne and Oxford and Cambridge were seminaries. They were in fact a forum for some individuals to advise people to opt for good rather than evil, and tell them what the truth is and what is permissible. They would talk and theorize.

Barbara W. Tuchman first released The Guns of August before penning The Proud Tower, which is a sequel to the Guns of August. Why did in Iran the translation of the second book come out first?

I have been asked the same question before. You can answer that question only when you hear the viewpoints of those who have read those books in reverse order. Each book contains information that forms a chain link in the minds of readers. That information link should exist in your mind for new links to be added to it. By reading this book one can answer some of the questions that pop up in their mind. The answer to each question might pose new questions.

The emergence of Capitalism in the US is linked to global wars for domination of lands. On the other hand, it can be regarded as an independent subject. Depending on the types of questions a reader might have in mind, they could find answers by reading these books. But I don’t suggest which one the readers should go through first.

These books are not textbooks and one is not necessarily a prerequisite for the other. The author had some questions in her mind, so she embarked on field research and subsequently wrote these books.

That a historical event is presented in the form of a story makes this book more appealing. The question is how close the book is to accurate history writing.

That question is for historians and those who put forth historical theories to answer. Just like linguistics, the theories researchers put forward vary and you may forget who said what in the past and whether it still holds.

Some people consider me a historian, but I am not one. I am just a translator, and historical texts are the same to me as any other subject.

We can’t help but look at the past through a modern prism. We can’t try to ignore what we already know. In The Sleepwalker, Arthur Koestler says, “We can add to our knowledge, but we cannot subtract from it. When I try to see the Universe as a Babylonian saw it around 3000 B.C., I must grope my way back to my own childhood.”

Koestler’s comment does not imply that Babylonians, who set up the first urban civilization, acted like children. They were wise people, but their knowledge was more limited than ours. A child’s knowledge about the world is limited, but they are mentally agile. When they learn something, they won’t forget it. Only through books and writing can humans develop an insight into abstract layers of the world and the truth.

Understanding that rotating a rectangle around one of its sides produces a cylinder is an example of abstract thinking. In order to appreciate spatial geometry, people in Babylon and Ancient Egypt and Mayans needed to be able to write.

We look at people who, let’s say, lived a century ago based on the information that is available to us. We know what has become of those people. Even without knowing what we know today, we can somewhat imagine in what conditions they lived. An abstract tightrope walking as such is only possible through texts and writing.

When the First World War was raging, people were not like us when it came to experience, habits and expectations. […] In directing movies which are set a century ago, an Iranian director knows about certain things that were customary back then, but s/he has to close their eyes to some of them to make the movie more presentable. Making judgment about the past with modern health criteria in mind is not what the director wants to do.

According to this book, in the scorching heat of the summer soldiers had to walk for long hours through the hills and woods each day. They wouldn’t get enough rest, nor were they given hot meals or proper gear including boots. In their diaries, German and French officers said stinking hungry soldiers had to walk almost half-asleep. Today nowhere in the world are soldiers treated that way. It is unimaginable.

Why do you think President John F. Kennedy gave copies of the book to his associates and suggested others go through it as well?

As far as I know President Kennedy gave copies of the book to members of his Cabinet and ordered more copies to be sent to US military bases around the world so that American officers could read it too. The book portrays individuals who wrongly assume they are in full control of things, but when they face a real emergency, they do not know what they should do.

I guess Kennedy knew that sometimes complicated things proved all too powerful for human intelligence to overcome. A military approach to a problem could have resulted in a nuclear war with the Soviets. He was worried about Communist China too.

In such a difficult situation one might make a decision that could transform the global landscape. Probably he didn’t want to be one of those politicians who had sent an entire generation of European soldiers to their deaths in the trenches 50 years earlier.

[…]