Nasrollah Pourjavadi, who holds a Ph.D. in Philosophy, founded Iran University Press in 1980 and remained at the helm of the publishing institution until 2003. Iran University Press released hundreds of scientific and research titles in the 23-year period he was in charge.

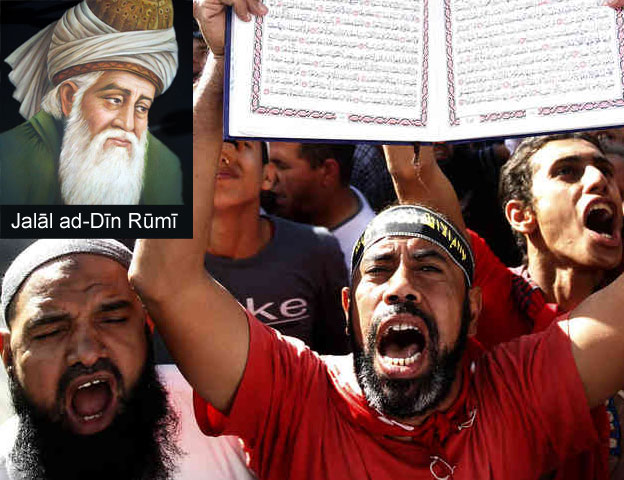

Dr. Pourjavadi has corrected or compiled tens of philosophical, literary and mystical books. In the following article published in a 17th issue of Andisheh Pouya (Dynamic Thought) Monthly, out in July 2014, Pourjavadi explains why Salafis are called what they are called and draws a line between Salafism as an approach and Salafism as a procedure. The same two concepts have been touched upon in two famous books by Mowlana – Fihi Ma Fihi and Mathnawi which use the character of one of the closest disciples of Prophet Muhammad to portray opposing states such as violence and compassion, war and peace.

In conclusion, Pourjavadi has a message for modern-day Salafis through the words of Mowlana, a message which is in line with Hadith – a saying that is attributed to Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.). The following is a translated version of the article in its entirety.

When humans get old, they rue the opportunities they have missed in earlier years, particularly in their prime. The same argument is valid about civilizations. When a civilization gets old enough to have its heyday in the past, people begin to envy the golden age. A similar feeling gripped Muslims three to four centuries after the emergence of Islam. Great men who were known as Friends of God suspected that the sun of Islam was setting and darkness was upon the Muslim faith. Abu Saeed Abul-Khair is said to have told a man of Zoroastrian faith one day, “There is nothing new in our faith today. What about your faith?” In other words, no more than 400 years into the dawn of the Islamic age, Abu Saeed thought the spirituality Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) had ushered in was on the decline. When a religion is already past its prime in 400 years or so, one which is 2,000 or 3,000 years old would definitely be on the brink.

After 400 years, people were already covetous of the time the Prophet was among them on the ground in Medina and gave everyone a chance to lay their eyes on him and savor the moment. Four centuries on, Muslims generally thought they were getting farther and farther from the reality of Islam. They would take great pleasure in seeing the Prophet and his infallible household in their dreams. There were vague ideas about those who had seen the Prophet and his infallible household in person and had tried to bring their words and deeds as close as possible to those of the messenger of God.

Different names such as the Companions, the Followers, and the Followers of the Followers were used to refer to individuals who had lived in the golden age of Islam. These individuals were truthful benefactors of the Islamic community and were described in Arabic as Salaf Saleh [competent predecessors].

That Muslims began to paint a picture of the so-called competent predecessors meant that the faith had its own history, a history in which some had developed an insight into the reality of Islam, a history that deserved to be coveted. In the fourth and fifth centuries AH (anno hegirae), there were a group of Muslims who were covetous of the past glory of the faith. These people who believed the sun of faith had already set or was sinking were called Salafis. They also believed that the golden age of Islam had come to an end and that truly faithful Muslims were part of history.

When the fighters returned home from the Battle of Badr and began to distribute the war spoils among themselves, Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) drew the attention of his followers to one of the most in-depth principles of faith. “We have just come from the Lesser Jihad to the Greater Jihad,” he said. When asked, the Prophet described the battle against the evil-provoking soul as the Greater Jihad.

Those first Salafis were pious, virtuous individuals who showed little interest in the material world. To them the world and whatever therein were worthless; in other words, the world was just a means to reach a loftier end: the afterlife. They likened the world into a farm and maintained that the crop of what was cultivated in it was to be reaped in the afterlife. They constantly dreamed of finding their way to the other world. For them the Companions of the Prophet were the ultimate role models. The Followers came next. The list of the most prominent Companions includes the Rashidun Caliphs including Imam Ali (Peace be upon him). To true Salafis, these four individuals were the closest to God after the Prophet. Their conduct was held up as a model of perfect behavior. Although Abu Bakr came ahead of Umar in rising to caliphate, the personality of the latter was far more appealing to the Salafis. Fihi Ma Fihi and Mathnawi by Mowlana bear testimony to such prominence in the eyes of Salafis.

On several issues, these two books are similar. Many of the things that appear in prose in Fihi Ma Fihi are mirrored in poetry in Mathnawi. As for Umar (579 – 644), the second Muslim caliph to take office after the demise of the Prophet, that is not the case, though. The things said about Umar in Fihi Ma Fihi are different from what is said about him in Mathnawi. Knowingly or unknowingly, Mowlana has painted two different pictures of Umar in these two books. In Fihi Ma Fihi, Umar is described as a non-Muslim who is forced into Islam by no other than Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.), a person who sets out to kill infidels immediately after converting to Islam. Mowlana makes an unbelievable claim about Umar and says that after becoming a Muslim, Umar killed his own father and just like modern-day Salafis paraded his severed head on the streets of Medina.

The story in Mathnawi is different, though. In this book, Umar is not violent at all. His character inspires awe, but is far from belligerent. In Mathnawi, Umar is a representative of the Prophet who settles the problems of the public. Instead of setting out to kill infidels, he shares spiritual secrets with the messenger of the Roman Kaiser and reaches out to the old man who plays the harp. He listens to the tune of Truth. It seems that Mowlana has been aware of duality in the character of Umar. He contends that Umar sought to use his sword to help the Prophet right after embracing Islam, but when he became the Muslim caliph, he put aside the use of force and began to promote virtue and advise the public to opt for the right path.

In Mathnawi, before narrating the story of Umar, Mowlana uses a saying attributed to the Prophet in order to explain this. When the fighters returned home from the Battle of Badr and began to distribute the war spoils among themselves, Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) drew the attention of his followers to one of the most in-depth principles of faith. “We have just come from the Lesser Jihad to the Greater Jihad,” he said. When asked, the Prophet described the battle against the evil-provoking soul as the Greater Jihad. Jihad (holy war) is what Islam instructs the faithful to wage. But against who? When Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W) was still alive, he said that as part of Jihad Muslims should take on their evil-provoking soul, carnal desires and wrath, as well as immorality. Jihad is not about hunting down the followers of other faiths including Christians, Jews, Buddhists and Zoroastrians – or Shiites as it is practiced today – with sword and sever their heads in front of their wives and children.

Those who believe that commitment to the Lesser Jihad is what religion is all about and those who wish to be part of the infidel-killing movement that emerged immediately after the dawn of the Islamic age don’t know and don’t want to know that if the Prophet had been among us today, he would have advised us against carrying out suicide bombings, killing Shiites and insulting the Western civilization. Instead he would have urged us to take on the evil-provoking soul and focus our attention on becoming true Muslims.

In Fihi Ma Fihi, Mowlana narrates a fictitious story: When Umar learned that his soul was his biggest enemy, he decided to drink poison to get rid of the foe within. He drank the poisonous cocktail, but he didn’t die. What the author is implying here is that Umar had identified his biggest enemy, but that he didn’t know how to take it on. He wanted to wage the Greater Jihad, but he was actually walking down the path of the Lesser Jihad. One needs to adopt a different method in order to embark on each of these two Jihads. You cannot take on the evil-provoking soul with swords, spears or poison for that matter.

Mathnawi is a book Mowlana has written on the battle against the evil-provoking soul. To Mowlana, the competent predecessors are the best of the faithful. But who are the competent predecessors? Those who embark on patricide and suicide? Or those who embark on promoting virtue after emerging triumphant in the Lesser Jihad? When Mowlana painted two distinctly different images of the competent predecessors, he viewed one as a hero of the Lesser Jihad and the other as the hero of the Greater Jihad. He knew that if the heroes of the Lesser Jihad were to be seen as role models, deviation would emerge and threaten the essence of religiosity. That was why he tried to paint a compassionate picture of the competent predecessors in Mathnawi. No doubt, back then there were some Muslims whose role model was a violent, sword-toting Umar. But Mowlana was of the opinion that such Salafist mentality posed a threat to Islam, so in Mathnawi he narrated a history of which spirituality and humanity were the hallmarks.

The threat that the world of Islam faces today is the same threat the Muslim Prophet tried to defuse by elaborating on the Lesser and Greater Jihads; the same threat Mowlana thought sword-toting Salafis were posing to Islam, the same threat that prompted him to paint a totally different picture of Umar. Unfortunately, the same threat, one which is even worse, is still out there today. The threat posed by Jihadist Salafis today has taken on more horrific proportions. Today they do not threaten people with clubs or swords; rather, they are equipped with the most destructive weapons of war. The thing they have forgotten is the Greater Jihad in which the faithful should take on the evil-provoking soul.

The Greater Jihad is not something passive or negative. It does not simply require you to lay down your arms. Rather, the Greater Jihad is proactive and affirmative in nature. If a religion did nothing to promote edification and human morality in order to bring its followers closer to God, it is not a religion at all. Those who believe that commitment to the Lesser Jihad is what religion is all about and those who wish to be part of the infidel-killing movement that emerged immediately after the dawn of the Islamic age don’t know and don’t want to know that if the Prophet had been among us today, he would have advised us against carrying out suicide bombings, killing Shiites and insulting the Western civilization. Instead he would have urged us to take on the evil-provoking soul and focus our attention on becoming true Muslims. That is what Mowlana talks about in Mathnawi. If he had been among us today, he would have urged the kind of Salafism he has talked about in Mathnawi, not the one that is portrayed in Fihi Ma Fihi.