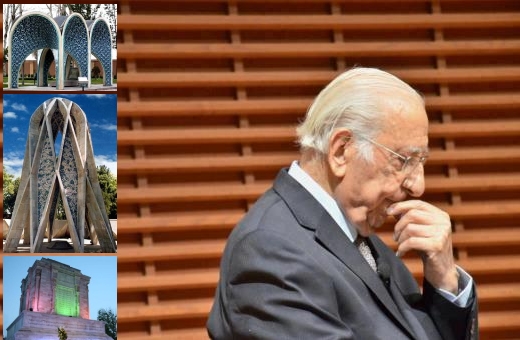

Houshang Seyhoun is a household name for people who are interested in Iran’s architecture. His artistic and architectural career which spanned over half a century is known to all Iranian culture and art lovers.

Under his belt, he has the experience of designing the Mausoleum of Omar Khayyam, and the tombs of Avicenna, Ferdowsi, Kamal ol-Molk, Nader Shah Afshar, Colonel Mohammad Taqi-Khan Pessian, and scores of immortal architectural works such as Toos Museum and Bank Sepah building in [Tehran’s] Toopkhaneh Square as well as lots of other residential buildings, paintings and Siah-Qalam works [the genre of paintings or drawings done in pen and ink].

Add to his tireless efforts years of teaching in the Faculty of Fine Arts in University of Tehran.He created a special architecture style in Iran by offering a harmonious and balanced mix of Iran’s traditional architectural styles and the modern technology-based style.

Shargh Newspaper in its July 14th issue published an interview with Seyhoun in which the interviewer, Ali Farasati, who is a faculty member at the California State University, has asked questions about the history of monumental architecture in Iran and around the world. It should be noted that Seyhoun passed away at the age of 94 on May 26, 2014 in Vancouver, Canada.

An abridged version of the multisession interview comes below.

The history of art and architecture is basically reviewed from two perspectives: pre-Islamic and post-Islamic. Do you think the two are distinguishable? If yes, what are their similarities? And if no, why is it so?

I do not see eye to eye with you on such a classification and I have some reasons for it. First of all, Iran’s architecture follows a continuous trend which has not stopped due to ideological, social and political ups and downs in the country. The preliminary documents on Iran’s architecture show a never-ending movement and a measured trend. T

hose, who seek to offer such a classification, cherish a presupposition or prejudgment which affects their judgment about artistic issues and the history of architecture. Architecture is not a phenomenon created instantaneously. We cannot say it is a chapter and what comes next is another chapter. […]

It is true that some architectural works such as mosques, religious sites, mausoleums and holy shrines serve religious purposes in society, but they are among national architecture as well. After the emergence of Islam, the Iranian architecture was the continuation of the very architectural activities Iran embraced before Islam.

Pre-Islamic Architecture in Iran

The oldest historical buildings in Iran date back 2,500 to 3,000 years. Are there any outstanding architectural buildings older than the remains of Takht-e Jamshid (Persepolis) and Pasargadae? I mean something which comes with special (hidden) architectural and artistic values. What are the standout features of these works?

Of the oldest historical buildings in Iran, one can mention Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat, which has the form of a [terraced step] pyramid. It used to be a temple with stairs leading to a door which opened to a site designed for worshipping. Bricks are the main building materials of the site. Some cuneiform texts have been found on the site, and some other writings seem to have been added to them later on. Pasargadae and Takht-e Jamshid are the other ancient works which have survived the passage of time.

On a path in Kangavar en route to Kermanshah stands a temple constructed by the Greeks. New mountain excavations, about 20-30 years ago, unearthed a Greek Hercules. We know of some other Greek temples elsewhere in the country, for example close to Kazerun, which have been built with stones.

Pasargadae and Takht-e Jamshid were built exactly when the Greek civilization and architecture were on the rise. Do you think these structures were inspired or affected by the Greek civilization in any way?

This question is raised by many. I don’t know about the origin of the idea that the Achaemenid architecture has been under the influence of Greeks. At any given time, an invisible wave surfaces in different parts of the world and results in the formation of unplanned,still unrelated, forms and conditions which in turn give shape to forms which conform to other works.

A structure similar to Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat in Iran can be found in Maya civilization in Latin America. It comes across as surprising that these two forms are very much identical as far as their appearance is concerned. This came as the Americas had was not discovered to people in the East back then.

Or the palaces and buildings the Achaemenid kings erected at that time conjure up similar ideas about the form of the Iranian and Greek architectures. A study of Shah Mosque, which was built in the Safavid era concurrent with the Renaissance movement in Europe, reveals qualities of architecture in Italian Renaissance, although the two forms of architecture were not related. […]

What has remained of the pre-Islamic Zoroastrian fire temples? How did those buildings look and what were their symbols?

I have no idea where the idea of fire temples has come from. I have been unable to find anything on this. The fact is that a fire temple is a special venue, a four-wall structure with a dome overhead, and the fireplace is at the center and below the dome. A few ancient fire temples still stand in the country, chief among them is Niasar Fire Temple in the vicinity of Kashan.

The monument has four sections with as many bases, forming a square and having a dome overhead. Many an ancient relief shows the image of this temple. Another fire temple sits near Pasargadae. […] Borujerd too is home to a fire temple which turned into a mosque after the advent of the Islamic age. It is still up and running there.

The Effect of Islam

Was it a technical need of the time to build a dome? Or was it significant because of climatic and symbolic aspects?

Dome was a technical necessity. There is direct correlation between buildings and architecture, and economy and money. That the Sassanid [kings] used the technique to provide covering for their buildings should basically have an economic reason.

Their predecessors, the Achaemenid people, used columns and stones for their structures, and for sure it was much costlier. Regardless of construction materials which were in abundance, the Sassanids worked out this solution to save time and raise construction speed. Naturally, their solution, which was vaulting in the form of domes, was matched with that time’s science and technology to prove workable.

[…] As for the second part of your question, I should say that the dome assumed a symbolic form in some cases, especially after the emergence of Islam. In Islamic architecture, a sky-blue dome in a spherical form amounts to reconstruction of thought directed at the heavens […]

Perhaps a metaphysical idea lies behind it, an idea which suggests the thoughts of an individual who believes in spiritual matters should ascend to the skies and to the infinite realm. And dome is a symbol for this.

[…]

How did Islam affect the Iranian architecture after it was welcomed in the country and what changes did it bring about? Did it exclusively affect the construction of religious buildings or did it leave its mark on other forms of art and architecture?

Islam has highlighted certain matters which deserve respect. It has also rejected certain things such as sculpting and drawing images on the buildings, especially on religious buildings. You know that the use of images, whether in the form of paintings and reliefs or sculptures, was common in religious buildings outside Iran such as churches and other Christian sites before Islam […]

In post-Islam Iran, this field of art lagged behind. Although this artistic field was conspicuous by its absence in the mosques, it was later replaced by other forms of art. The Iranian artists cannot sit idly; they need to unleash and express their inner feelings one way or another.

Sculpting was banned but the Iranian artists turned to geometry, calligraphy and other forms which were mostly abstract. Much of what they did in new ways was artistic masterpiece.

What Is Iranian Architecture?

Generally, can we employ the term “Iranian architecture” for Iran which is a multiracial country with a climatic variety?

Well, since Iran sits on a limited geographic expanse of land, whatever happens within it should be named as “Iranian architecture”. The difference between Iran and other countries lies in Iran’s geographic and climatic variety. For instance, northern Iran is a green, humid area with high precipitation, whereas central and southern Iran is dry and hot, with no lush green areas.

Naturally, different climatic conditions call for varying architectural styles. This is why the architecture used in the mountainous areas distinctly differs from that in the desert; in other words, the former cannot be implemented in the desert. […]

Based on ancient works and apparent differences in style, the history of Iran’s architecture following the Sassanid era can be placed in eight distinguished periods: the Arab rule, the Sassanid, the Saljuq, Mongols, the Safavid, the Zand dynasty, the Qajar and the Pahlavi. Do you approve of this categorization? How do you define the indicators of each?

To introduce the staggered architecture history, one needs to employ the tags used for different government types. As the history of societies ran their course, each period created their own artistic works, among them architecture, under the influence of economic, social and cultural factors of the time. So such staggering cannot be opposed because they were realities which had taken place and they are out of our control and beyond what we wish.

The fact is that many things have happened during each of these periods under the influence of which architecture too has experienced some ups and downs. […] All through these periods, we have witnessed a fixed, still continuous and forward-moving trend in architecture.

This was the case until the Qajar period which saw Iran’s artistic and cultural activities wane, but toward the end of the Qajar period and the first years of the Pahlavi era the global architecture underwent drastic turbulence due to the Industrial Revolution and scientific developments in Europe. Out of such big changes the modern architecture was born.

The Effect of European Styles

Each period of Iran’s architectural history, especially the recent history, has been concurrent with one of the European architectural styles. Are the effects of such styles traceable in the Iranian architecture, I mean especially in the period following the Safavid kings up until now?

Yes. Iran has been affected by the European styles in many cases. It is quite evident not only in architecture but also in other cultural aspects. For example, religious ceremonies such as holding special mourning sessions and Ta’zieh Khani which are usually done today were not customary before the Safavid period which introduced such ceremonies to Iran’s religious culture.

Ta’zieh Khani reached its peak in the Qajar period because the Qajari kings established more ties with foreign countries, and religious theaters of Italy and other European nations influenced Iran’s ceremonies. Ta’zieh Khani is, in fact, a tragic opera because you can see acting, costumes, icon-making, music and singing in it. […]

Back then, the (Qajar) shah would travel to Europe quite often […] Affected by operas and ballets there, the shah brought shaliteh (short creased skirts) and tights to Iran. Women in his Haramsara started to use these items. Everything was under the influence of Europe from architecture to clothes, columns and plaster works which were in style at that time.

Plasterwork is popular again today despite all the changes it went through. The effects are usually related to those parts that were absent before. But when it comes to the Safavid architecture including Masjed Shah, Ali Qapu, Chehel Sotoun (Forty Columns), Hasht Behesht (Eight Paradises) and Isfahan bridges, they are one hundred percent Iranian.

The End of Iranian Architecture

In books on the history of world architecture, the Iranian architecture comes to an end with the Zand dynasty. Is there any remarkable work afterward, something which could be internationally presentable? Or is it true that the Iranian architecture, as historians have put it, came to a stop back then?

Firstly, the Zand dynasty was in power for a short period, thus not so many architectural works originate from that period. However, a small number of works which have remained from the period in question are architecturally remarkable and represent their own era. These works are viewed as historical monuments such as The Vakil Mosque (Masjed-e Vakil) and Quran Gate (Darvazeh Koran) in Shiraz.

The Qajar period, however, saw Iran decline. The country suffered huge backwardness. […] Certain remarkable structures have remained from this era, though. An example of this is the Great Timcheh of Qom which is related to the Qajar period and is one of Iran’s national architectural masterpieces.

If you leave Tehran for Kashan, when you drive past Qom, before the very end of the road, you will see the bazaar and Timcheh on your left. It is very beautiful. There is nothing on the outside and all is inside. The interior part has been delicately built with bricks as if it were needlework. The structure contains three domes which have been created through geometrical forms and arches and curves. Looking at it, one may think how delicately a big opening has been covered with tiles. […]

Thanks to technological and scientific developments, especially after the First World War, architecture underwent changes in the Pahlavi period. The initial years of that period, affected by a special sense of nationalism and inspired by ancient Iran, the Achaemenid and then the Sassanid, witnessed their works copied and duplicated since the Pahlavis regarded the Achaemenid as the beginning of ancient Iran.

Drawing on such a mindset, they created some works, including the Tehran Police Department, Bank Melli, the first building of Ferdowsi Tomb which I renovated, Anoushiravan Dadgar High School, the old Muze-ye Iran-e Bastan (Archaeological Museum of Iran), and the like. The construction of all these structures was affected by the architecture of ancient Iran, something I think was wrong.

On the other hand, the progress of Iran had taken on a modernist form and this question was hotly debated right then. This can be found in the poems of Aref (Qazvini), Mirzadeh Eshghi, Malek al-Shoara and Iraj Mirza. Some of the buildings which were constructed in Reza Shah Period like the railway station, schools and University of Tehran were basically made by foreigners, especially the Germans and French.

If you take a look at the ceiling of the railway station in Tehran, you would see a Swastika in which the lines have been distorted creating a new image. Some schools such as Ferdowsi, Firuzkuhi and Noorbakhsh high schools were designed and built by the French. This makes it clear that it was the Qajar dynasty which started the Westoxification movement and it was continued by the Pahlavi shahs.

A tendency toward the West which emerged rapidly in a short time span denied Iranian architects the opportunity to implement Iran’s modern architecture with the help of Western techniques. […]

Later when the Faculty of Fine Arts was built, especially when it was managed by Iranian architects, it held seminars, conferences, and tours and offered special training courses, as the Iranian architecture style was given more attention as it tried to use new techniques.

Then efforts got underway to identify Iran’s noble art and architecture, survey historical monuments, and organize trips by university students and professors to the four corners of the world and to remote villages in order to discover the hidden aspects of the culture and art of the Iranian architecture.

No Remarkable Landmarks in Tehran

Kings of different dynasties tried to build and develop areas around the capital, like the Safavid in Isfahan and the Zand in Shiraz. But no remarkable landmark is seen in Tehran which was the Qajari capital. How do you explain that?

The buildings which were built in Tehran during the Qajar period are as follows: Sepahsalar Mosque, Golestan Palace, part of the bazaar and several other mosques such as Shah (now Imam Khomeini) Mosque. Unfortunately Reza Shah took some wrong measures among them the destruction of Tehran gates. […]

As you know, Tehran became the capital of Iran in the Qajar Period. Before that Tehran was just a village on the outskirts of Shahr-e Rey. It was located between Shahr-e Rey and Shemiran Village. The Qajar kings chose Tehran as their seat of government and as it was customary back then, they dug deep ditches around the new capital because Tehran was the target of enemies.

By doing so, they wanted to defend themselves. They built 13 gates on the ditches to control entry into and departure from the city. The amazing gates stood out in the area.

Unfortunately these gates are not in Tehran any more. Similar gates are still functional in Qazvin and in Semnan. Niavaran Palace too was one of the buildings constructed in the Qajar period which was repaired and reconstructed during the rule of Mohammad Reza Shah. It also housed the offices of the shah. […]

The capital of Iran is almost as old as that of the US but the two cities differ greatly as far as the urban development, buildings and attitude toward building the capital city are concerned? What’s your take on that?

We shouldn’t compare Washington with Tehran because each has been created under special circumstances which are not similar at all. Just like Paris, the US capital is a city designed by French developers. […] Another point is that the US adopted policies in keeping with its economic and technological demands.

In Iran, Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar hailed from a nomadic tribe. He sought not to be within the striking distance of his enemies, the Zand kings, so he selected Tehran as the seat of his government on military grounds only. He wanted to remain close to his tribe in Astarabad and the high mountains nearby which could serve defensive purposes in case of a possible withdrawal.

At first Tehran was more like a military sanctuary. By and by new buildings were erected without any planning. […] If you have a bird’s-eye view of the city’s old fabric, you will see a set of small, similar houses linked by narrow, dark alleys. Contrary to Washington, there was no planning for urban development in Tehran.

In fact, Tehran was a village which had grown lengthwise and widthwise in the same manner as a village did. Over time buildings rose to lay out streets for the city’s administrative, economic and security purposes. The streets met the traffic needs of the time, but now they fail to keep up with the demand of the current population, and thus the traffic congestion.