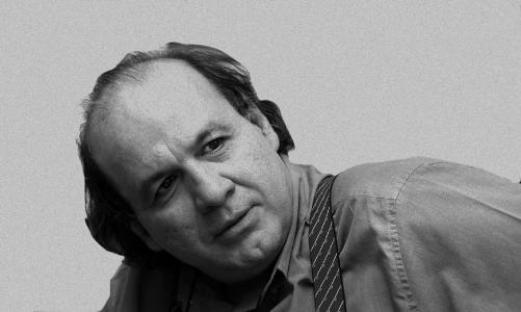

It is almost a year since the use of the terms moderation and restraint has picked up in our daily conversations. When Dr. Hassan Rouhani used the same words to paint a picture appealing enough to the Iranian people to hand him an emphatic victory in elections, the question was whether moderation could turn into common discourse in Iranian culture. Anthropologist Nasser Fakouhi answers that question and talks about the application of moderation in formulation of cultural strategy. The university professor believes moderation is tantamount to rationalism and wisdom and says: “In order to institutionalize the culture of moderation and develop a cultural strategy on its foundation, the first step should be to erase the myth-ridden mentality that has ensnared us in the radical and conservative ideologies of the 20th century. Today the nationalist ideology is not touted anywhere in the world; and in case there is any such promotion, it comes from the least developed sections of society.” The following is an excerpt of an interview a 44th issue of Jostoju, the monthly appendix of Etemad newspaper, conducted with Dr. Fakouhi, an assistant professor at Tehran University’s Faculty of Social Sciences:

Last year saw the victory in presidential elections of a candidate who ran on a platform of moderation in politics. The question is how moderation caught the eye of the Iranian people. Was it already an attribute of the Iranians? Basically, are the Iranian people known for having such a characteristic?

The change in question should come slowly and steadily to minimize risks and repercussions in the short- and medium-run.

The approach we have Iranized and renamed is well-known in our own culture and in cultures elsewhere in the world. It’s not anything new, neither in politics, nor in social behavior. As far as social behavior is concerned, moderation is a rather vague concept with more or less clear characteristics. It prompts us to distance ourselves, on the one hand, from radicalism (recourse to disproportionately extreme views to change the status quo) and, on the other, from conservatism (tendency to maintain the status quo) and accept the fact that thanks to clearly explainable reasons the status quo should change for the better (to secure public satisfaction and improve the quality of their lives). However, the change in question should come slowly and steadily to minimize risks and repercussions in the short- and medium-run.

Are you suggesting that during last year’s presidential elections we understood that the change in question should be introduced with moderation?

In addition to plots by foreigners, we fell prey to radical and conservative discourses and missed out on a great opportunity.

As I said this approach is deep-rooted in our traditional culture and in cultures elsewhere in the world. Its root should be looked for in an experience which has led to the emergence of a practical philosophy. I don’t want to get involved in lengthy political and theoretical issues here, but it’s worth mentioning that rightist revolutionary approaches of the 20th century (Fascism, and most recently Thatcherism, and Reaganism which outlived President Reagan and stretched into the Bush presidency) and leftist approaches (Leninist and Maoist Communism and Castroism) were jarring examples of dangerous radicalism and conservatism that led to dire consequences for societies, and the world at large. Other ideologies on the left side of the spectrum such as Social Democracy and on the right including Christian Socialism are clear examples of leaning toward moderation. In other words, we have both historical and theoretical examples to deal with. In response to your question as to whether Iranians have been familiar with such approaches, I would have to say: without a doubt. But just like people elsewhere in the world they are as exposed as ever to the other two tendencies. And the reason for that is clear: radical and conservative discourses are abbreviated worldviews that simplify everything and thus catch the eye of more individuals. In fact, they show the audience a green-light that is non-existent. Whereas the discourse of moderation always has to display intricacies and difficulties as an inseparable part of the package it offers. A perfect example of this happened during Iran’s Constitutional Revolution and later during the nationalization of the oil industry. In addition to plots by foreigners, we fell prey to radical and conservative discourses and missed out on a great opportunity. […]

Can we make a nation buy into moderation as a cultural strategy or a cultural characteristic? And what should be done to pave the way for such acceptance?

It is not a national characteristic. I have said this in the past, let me repeat myself, recourse to national sentiments and nationality, to which we are accustomed, is something political. This theory which was championed by Anthony Smith and Benedict Anderson, who lived around the time of the French Revolution, is less than 200 years old. In Iran, the most optimistic historical perspective would suggest that it dates back to the time when the Constitutional Movement was in the making. What we pay attention to is the Iranian civilization and culture that goes back thousands of years and manifests itself in the language, lifestyle, wisdom and thoughts, philosophy, technological skills, intelligence and survival strategies of the people. It has nothing to do with governance in general and vulnerable national governments whose reigns had barely hit the 100-year mark in particular.

We need to focus on these cultural elements in building our future and not on a nationalistic mythology that is a product of the racist policies of the 20th century which have done nothing of significance for humanity except overseeing the killings of hundreds of millions of people and commission of unspeakable atrocities.

The vulnerability you just mentioned is of great importance. What can be done to get rid of the mentality of which myths are a central part?

I believe the first step down that path should be toward elimination of the myth-ridden thoughts that hold us hostage to radical or conservative ideologies of the 20th century. Today nationalist ideology is not touted anywhere in the world; in case there is any such promotion, it comes from the least developed sections of society. For example, recent European electionswhich saw the resurgence of nationalism in countries such as France were widely dubbed as a grave threat. In our country a bunch of individuals who view themselves as masters proudly lay claim to Fascist and other racist ideologies without drawing any criticism. These individuals hijack our history and nurture the idea of setting up imaginary governments which would inflame ethnic and racial hatred and shed blood across the land if and when they rise to power. That is why I think the first step is to rid ourselves of such problems that first found their way into our society more than 100 years ago. We need to develop an understanding of the world the way it is, rather than the way we want it to be. Such understanding is key to securing our rightful place in the community of nations. Narcissism and self-doubt are the biggest threats against nations and the Iranians are under threat from both.

Is there any link between culture and the birth of moderates in a society?

No one is born a moderate, or a radical for that matter. Biologically humans might have features that render them predisposed to a certain line of thinking, but culture is there to help bring up social creatures poised to accommodate others and accept that human beings cannot exist in vacuum.

I didn’t mean biological birth. Can culture be used to raise moderate individuals?

Culture is the best means to change individuals’ predispositions to violence and non-accommodation of others. In social systems, selfishness is bound to bring about destruction, whereas selflessness guarantees sustainability.

In light of Iran’s political developments over the past two decades, can the victory of a candidate that ran on a platform of moderation institutionalize restraint in society? The election in June 1997 of Seyyed Mohammad Khatami was an idealistic choice of the public which was followed eight years later by a vote that placed Ahmadinejad at the helm of the executive branch. Are the results of last year’s elections an indication that moderation is gaining momentum in our society?

I believe those two developments you just mentioned, particularly the 9th and 10th governments [led by Ahmadinejad] which openly supported radicalism and populism and dealt an unspeakable blow to the country, have been instrumental in this [promotion of moderation]. People witnessed that one can easily make promises and shatter livelihoods. They found out that it was easy to make a mockery of the world and force an entire nation to live with the colonial, domineering policies of big powers who used the same empty promises to justify their actions. The tough stance taken in the face of big powers produced nothing but sanctions and back-to-back resolutions against the Iranian government. That was a reality major powers had failed to swallow ever since the victory of the Iranian revolution. Until the rise to power of the 9th government, they had not found the opportunity to bring so much pressure to bear against Iran through sanctions and resolutions. How did they do it? How was it possible for a widely-loathed racist government like that of Israel and a warlike administration like that of President Bush to easily talk about military option against Iran? The reason is obvious. They were dealing with a radical who used very harsh words they blew up to justify their actions. I believe today Israeli and American hawks frown upon the discourse of moderation. Why is a group, willingly or unwillingly, inflaming tensions in the country to set the stage for them [hawkish Israeli and US politicians] to redirect their warlike slogans at Iran? That is when their economic interests come into play. A raging crisis is ideal for those who think about nothing but plundering the country’s resources. […] Everyone who inflames tensions is willingly or unwillingly serving the interests of major powers in this restive corner of the world. We are among a handful of countries which have remained immune from the cycle of violence. Moderation is not a political or ideological choice – rather it is a wise, strategic necessity.

A look at Iran’s history suggests that sometimes Iranians do not put up much resistance in the face of heavy attacks and later come to terms with the aggressors. What is your take on such an attitude? Is it in any way related to institutionalization of a characteristic in society?

That is another rather vague idea one cannot rule out. A glance at the history of Iran shows that it is true, to a large extent, but it cannot be used as a basis for drawing practical or short- and medium-term conclusions in modern and post-modern circumstances. What Iranians did 500 or 1,000 years ago does not have anything to do with what they should do today, unless we develop an insight into their strategic thinking and build on their thoughts to formulate a modern-day strategy. Such an approach requires high levels of intelligence, top management skills and a deep understanding of the world. Although history helps, it does not provide us with any example to imitate, neither in Iran, nor anywhere else in the world. In a very complex way, cultural strategies can either propel a civilization in the course of history or lead it to the brink of annihilation. The point we need to pay attention to is that there is no autopilot. The future lies in our own hands. Depending on the amount of effort and energy we put in, Iran can turn intoone of the most developed countries of the globe, or come down in the world. In contemporary history we have seen both cases unfold in civilizations with a long history just like Iran’s. We need to act vigilantly and build on wisdom in choosing our future path. We need to make sure we are not tempted to disregard other countries and cultures or the variety that exists within Iran, a variety that manifests itself in the lifestyle, education and identities of individuals. Such variety could be our biggest asset if we develop the capability to tap into it. On the other hand, it could turn into a grave threat if we assumed that all people should be like each other and their lifestyle, ideas and behavior should be in keeping with a strict unified model.

We need to respect the rights of minorities and avoid fabrication, hypocrisy, corruption, acquisitiveness, extravagance and of course indifference toward the plight of others. That holds the key to our success and that of moderation.

No doubt, what we call social cohesion, coexistence, and possession of national and cultural identity entails certain requirements such as compliance by all members of society with a set of ethical, legal, and traditional standards. But how we interpret these rules and put them into practice can dramatically change our destiny. I believe the kind of management that draws on a social system, rather than take it on or put pressure on it, can create a good atmosphere for all citizens or at least for a majority of them in which freedom, equality, and justice – which have always been stressed by our traditions and religion – are the key principles. In other words, we need to respect the rights of minorities and avoid fabrication, hypocrisy, corruption, acquisitiveness, extravagance and of course indifference toward the plight of others. That holds the key to our success and that of moderation.